Data Center Stories

Data Center Stories

From Grok, how top non-fiction authors would tell one story of data-center cooling

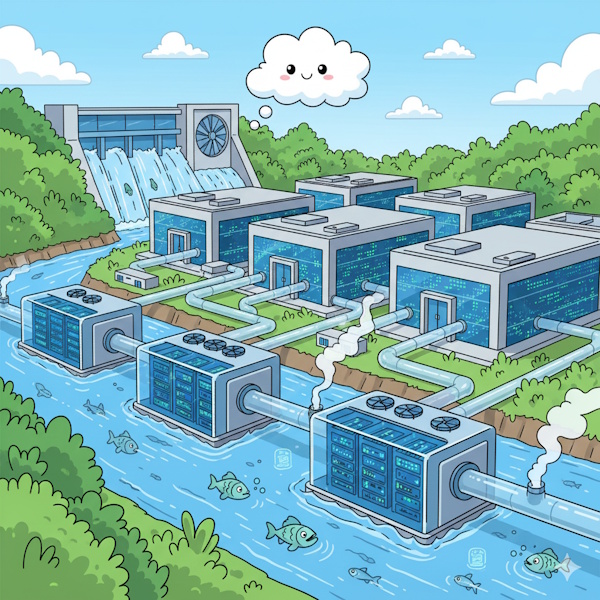

Big tech's rush to build AI-ready data centers in Oregon is colliding with a tightly stretched, legally complex water system in and around the Deschutes River Basin in Oregon. The result is a growing tension between the global cloud infrastructure and a fragile river-aquifer network that is already under stress from drought, irrigation, endangered species protections, and groundwater decline.

The River That Forgot How to End

Plot (in three acts)

Act I - The Disappearance

Summer 2025. The Deschutes River, one of the last free-flowing jewels of the American West, literally runs dry for the first time since Lewis and Clark floated past in 1805. Farmers lose crops, Native fishing sites turn to dust, and the Bureau of Reclamation issues bland statements about "drought." A freelance journalist (the narrator) stumbles on a leaked water-usage spreadsheet showing that the new hyperscale data-center campus outside Prineville is pulling more water than the entire city of Portland. The numbers are classified; the campus is owned by a nest of shell companies. The river's death looks legal on paper.

Act II - The Quiet Saboteur

The narrator tracks down a former data-center technician named Caleb Morrow, now living off-grid in a trailer. Caleb reveals he spent eighteen months inside the facility slowly, almost undetectably, bleeding millions of gallons of cooling water back into the desert. He never tripped an alarm, never caused an outage, never asked for money or fame. His only tools: a Leatherman, a burner phone for anonymous tips to tribal water attorneys, and an almost pathological patience. Interwoven are flashbacks to 1924, when government surveyors declared the Deschutes "inexhaustible," and to the secretive land-and-water deals of the 2010s that quietly transferred century-old rights to tech giants.

Act III - The Aftermath

The sabotage is eventually discovered (not by corporate security but by an IRS audit of a Cayman trust). Caleb disappears the night before federal agents arrive with a warrant. The company spins the water loss as "sensor error," pays a modest fine, and breaks ground on Phase IV. The river stays dry. In the final scene the narrator stands on the basalt rim with Caleb's abandoned photocopy of the 1924 survey fluttering in the dust. The data center's cooling towers glow on the horizon like a new mountain range that never casts a shadow.

Main Characters

Caleb Morrow

29-32 across the story. Former night-shift critical-facilities tech. Grew up on a failing family ranch; knows irrigation math the way other kids know video-game cheat codes. Quiet, methodical, speaks in short sentences that land like dropped wrenches. The closest thing the story has to a hero, except he never thinks of himself that way.

Priya Desai

Mid-30s. Lead thermal engineer for the campus. Born in Mumbai, PhD from Stanford, once designed cooling for nuclear submarines. Brilliant, exhausted, and the only senior employee who quietly helps Caleb by looking the other way. She never joins his sabotage but never reports him either.

Edgar L. Hampton (1889-1961)

Ghost character. The 1924 government surveyor whose field notes ("water plentiful, clear, and cold...appears inexhaustible") become the ironic refrain that runs through the book. Caleb carries a photocopy of Hampton's page the way soldiers once carried letters from home.

"Mr. Volterra"

Never appears in person. The anonymous beneficial owner behind the Cayman trust. Rumored to be a consortium of three Big Tech founders who needed a place to train the next generation of foundation models without anyone noticing the water bill.

The Deschutes River itself

Functions almost as a character: once wild, now a patient that has been quietly bled out by a thousand small, legal cuts.

Read: Jon Krakauer | Erik Larson | John McPhee | Mitch Albom | Truman Capote | Mary Roach | Joan Didion | Cat Bohannon | Patrick Radden Keefe | Michael Lewis | David Grann

|

Jon KrakauerThe Mountain That Eats the Sky |

They call it Prineville Block 27, but it has no address, no mailbox, no welcome mat. Just a mile-long rectangle of corrugated steel squatting on the high desert of central Oregon like a spacecraft-gray, windowless, humming. From the air it looks like a misplaced aircraft carrier stranded among sagebrush and juniper. Up close it is louder than you expect: a constant, low, animal roar, the sound of forty thousand fans inhaling the thin, cold air of the plateau and exhaling it again as heat. The building drinks 120 megawatts of electricity every day, enough to run a city of a hundred thousand people, yet not a single human being lives inside its walls.

I came here in the winter of 2024 because I wanted to understand what we had built. Not the cloud, that lazy metaphor, floating euphemism, but the actual thing: the furnaces where our photographs, our secrets, our TikToks, our wars, our love letters, our lies are burned into silicon and cooled with water stolen from dying rivers. I wanted to stand in the cold aisle and feel the heat on my face and ask the same question no one in Silicon Valley wants to answer: What does it cost to keep ten billion human lives running inside machines?

The man who let me in was named Caleb. Thirty-two years old, raised on a cattle ranch twenty miles away, now a senior technician for one of the five companies whose logos you've never seen on the building. He wore a black hoodie and the kind of exhaustion that never quite leaves the eyes. We met at 5:00 a.m., when the temperature outside was four degrees and the temperature inside the cold aisle was sixty-four, exactly, always.

"Ready?" he asked, swiping his badge. The door sighed open like a walk-in freezer. The roar hit first, then the smell: ozone, hot dust, and something faintly metallic, like blood warmed by a fever.

Row after row of black cabinets stretched into the dark, each one seven feet tall, each one breathing. Blue LEDs blinked in slow, the heartbeat of something alive but not conscious. Caleb walked me down the aisle between them. The floor vibrated under my boots. The air was so dry my lips cracked in minutes.

"Every cabinet holds forty-eight servers," he said, raising his voice over the white noise. "Each server has two CPUs that pull four hundred watts apiece. Do the math."

I did. One cabinet: thirty-eight kilowatts. One row: maybe four hundred cabinets. One pod: eight rows. The building has forty pods. The number is too large to hold in a human mind, so the mind does what it always does with enormity: it turns away.

Caleb didn't turn away. He had been inside these buildings for nine years, long enough to watch the desert change. When he was a kid, the night sky over Prineville was black enough to read by starlight. Now the data centers, there are eight of them here, soon twelve, throw a glow you can see from fifty miles. On certain winter nights the sky above the plateau is the color of a dying television.

We reached the end of the cold aisle. Caleb pointed to a steel grate in the floor. "That's where the water goes," he said. The centers pull 350,000 gallons a day from the Deschutes River to cool the chips. In a normal year the river barely survives irrigation. This is not a normal year. The snowpack is gone by April. The farmers downstream are furious. The fish are dying. But the centers have senior water rights, bought decades ago by ranchers who never imagined their grandchildren would sell the future for stock options.

I asked Caleb if it bothered him.

He thought for a long time. "I used to think we were building the library of Alexandria," he said finally. "Now I think we're building the furnace that burns it."

Later that morning we drove out to the edge of the complex, where a new pod was rising: a skeleton of steel beams against the pale sky. The construction crews worked in silence, their breath fogging in the cold. Beyond the fence, a lone pronghorn antelope stood on a ridge, staring at the thing we had planted in its winter range. It did not run. It simply watched, as if trying to understand what kind of animal makes a mountain that eats the sky.

I thought of Chris McCandless starving in the Alaskan bush, scribbling in the margin of Doctor Zhivago: "Happiness only real when shared." I thought of the climbers frozen on Everest, chasing a summit that never cared whether they lived or died. And I thought of the billions of human moments, funny, cruel, tender, trivial, stored in these humming boxes, cooled by a river that will not last another lifetime.

The machine is magnificent. It is also, unmistakably, a tragedy in real time. We just haven't decided yet who the victims will be.

Caleb lit a cigarette outside the guard shack, hands shaking from the cold or something else. "Sometimes," he said, "I dream the fans stop. Just for a second. The whole world goes quiet. And in that second I can finally hear the desert breathing again."

He dropped the cigarette, ground it under his boot, and walked back inside to keep the furnace burning.

I stood there a long time, watching the smoke rise into the Oregon sky, thin and pale against the glow that never goes out.

|

Erik LarsonThe Devil in the White Box |

Chicago, September 1893. The World's Columbian Exposition glittered along the lakefront like a dream made of plaster and electricity. One hundred and thirty-one years later, almost to the day, another white city rose on the high desert of central Oregon, only this one was not built for wonder but for memory, and its architect was not Daniel Burnham but a quiet, relentless force named electricity.

The place is called Prineville Block 27. To the untrained eye it is merely a very long, very gray warehouse set amid sagebrush and juniper, windowless, anonymous, humming. Yet inside its steel skin, on the morning of March 14, 2024, something extraordinary was about to happen, or rather, almost fail to happen, which in the strange new physics of the twenty-first century is often the same thing.

At 6:17 a.m. Pacific time, a technician named Caleb Morrow, age thirty-two, father of two, former high-school quarterback turned guardian of the cloud, noticed an anomaly on Pod 19's temperature dashboard. The reading in Rack 42U climbed from the usual 72.4°F to 79.1°F in ninety seconds. A small jump, barely a hiccup to a human body, but to the 1,536 GPUs inside that rack, each one running at 350 watts, it was the difference between calm computation and a miniature inferno.

Caleb had seen worse. In 2022 a squirrel had shorted a transformer outside Reno and taken half of TikTok offline for eleven minutes. The internet had howled like a wounded animal. Yet this morning felt different. The outside air was four degrees below freezing, perfect for cooling, and still the rack was heating as though someone had opened an oven door inside the building.

He radioed the control room. "We've got a hot spot in 19. I'm going in."

The control room supervisor, a woman named Priya Desai who had once designed cooling systems for nuclear submarines, answered with the calm that masked alarm. "Copy. Take the crash cart."

Caleb wheeled the red metal cart down the cold aisle. Forty thousand fans roared overhead like a perpetual jet engine. The floor vibrated through the soles of his shoes. He reached Rack 42U and stared up at the blinking blue LEDs that normally pulsed in gentle rhythm. Now they flickered in frantic Morse.

He opened the rear door. A blast of heat rolled out, carrying the sharp smell of hot silicon and fear. One of the CRAC units, computer room air conditioners the size of boxcars, had failed at 6:09 a.m. A single bearing in a $220,000 blower motor had seized. In the seven minutes since, the temperature had climbed another four degrees.

Priya's voice crackled in his ear. "You have ninety seconds before thermal throttling starts. Two minutes after that we lose the GPUs. Four minutes after that the lithium-ion batteries in the UPS room hit thermal runaway. You know the rest."

Caleb did. He had run the simulation a hundred times. A fire in a hyperscale data center spreads at the speed of rumor. The sprinklers are deliberately weak; too much water and you drown a million servers. The halon gas system can smother flame but not before the heat warps the chips into useless foil. Insurance adjusters call it a "total loss event." The industry prefers the term "black sky day."

He climbed the rolling ladder, popped the blower panel, and reached for the spare bearing assembly clipped to the crash cart. His hands, normally steady, shook slightly. Not from cold. From the knowledge that at that exact moment, somewhere in the world, a teenager in Lagos was uploading her first song, a grandmother in Kyoto was video-calling her grandson in Sao Paulo, a surgeon in Stockholm was guiding a robot through a heart valve repair, all of it flowing through the chips he now held in his palm.

He slid the new bearing home. The motor whirred, caught, roared back to life. Cold air flooded the rack like a prairie wind. The temperature curve on his tablet bent downward as gracefully as a swan diving into a lake.

Priya exhaled across the radio. "Good work, Caleb."

He closed the panel and allowed himself one breath of relief. Then he looked up at the endless rows of cabinets stretching into the artificial night and felt something colder than the Oregon morning settle in his chest.

Because the truth, the one no one in Silicon Valley liked to speak aloud, was that the entire civilizations now balanced on the edge of a single ball bearing.

Later that afternoon, under a sky the color of tarnished nickel, Caleb stood outside smoking a cigarette he had promised his wife he would quit. In the distance, construction cranes erected the skeleton of Prineville Block 28, twice the size of the building behind him. Beyond that, Block 29. And 30. Each one destined to drink more power than the city of Bend, each one guarded by men and women like Caleb who understood that the cloud was not a cloud at all, but a new kind of city, vast, fragile, and burning.

He flicked the cigarette into the snow and watched it die with a hiss.

Somewhere inside the white box, forty thousand fans kept breathing, keeping ten billion human lives alive for one more day.

|

John McPheeThe Servers of Prineville |

The building is a third of a mile long and looks, from the county road, like a very clean, very long shed that someone forgot to put windows in. It sits on the Crooked River basalt, elevation 2,870 feet, where the junipers grow low and the wind moves in straight lines across the high desert. The sign at the gate says only CROOK DATA CAMPUS. No company name. No logo. Just a small blue sticker that reads BADGE IN - BADGE OUT.

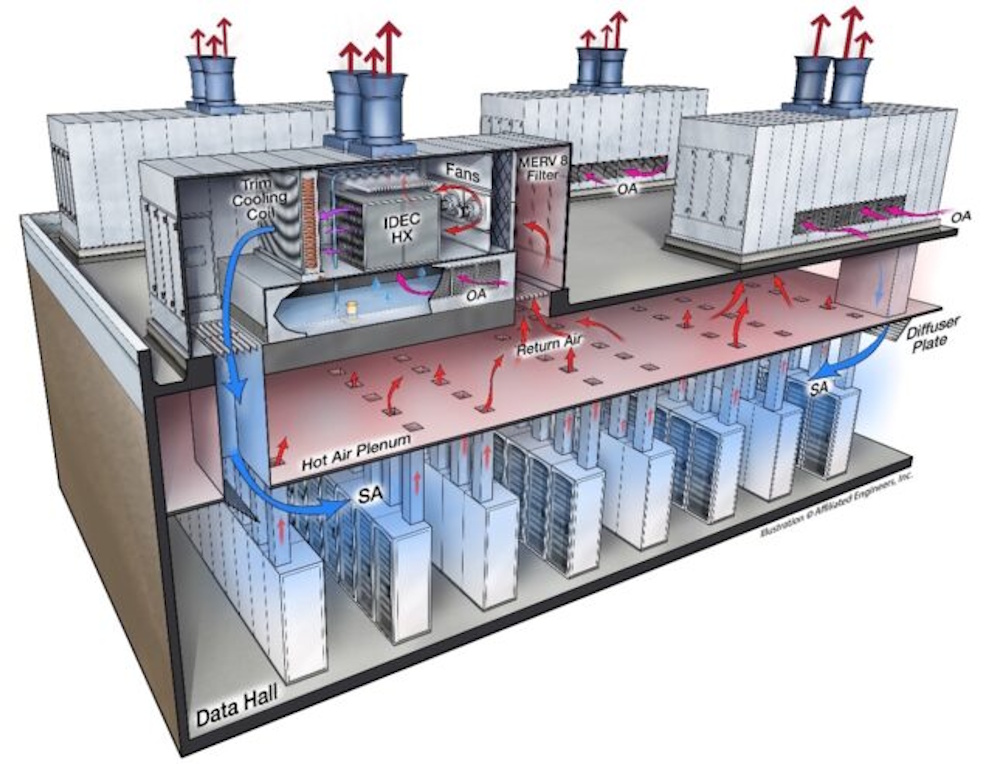

Inside, the air is sixty-four degrees and twenty-five percent humidity, always. The floor is raised eighteen inches, a steel grid over a plenum that carries cold air upward the way a chimney carries smoke. Under the floor run trays of fiber-optic cable the color of margaritas, each strand thinner than a human hair and capable of moving forty terabits per second. Above the floor stand the racks: black, seven feet tall, forty-eight servers to a rack, eighty racks to a row, eight rows to a pod, forty pods to the building. Do the arithmetic and you arrive at a number that feels less like engineering and more like astronomy.

The servers themselves are quiet. The noise comes from the fans - forty thousand of them - turning at twenty-two hundred revolutions per minute, pushing air through fins so tightly spaced that a sheet of paper will not pass. The sound is not loud in the way a jet engine is loud; it is loud in the way the ocean is loud when you stand inside it.

I spent a week walking the aisles with a technician named Caleb Morrow. He grew up on a ranch ten miles east, where the only lights at night were stars and the occasional pickup on the way to town. Now he spends his shifts among machines that never sleep. He knows every rack by its temperature curve the way a shepherd once knew every sheep by its face.

On the third day he showed me the cooling plant. Six chillers the size of ranch houses sit outside the west wall, each one containing a thousand gallons of refrigerant that boils at minus forty degrees Fahrenheit. The chillers pull heat from water that has passed through the cold aisles, then send the chilled water back in a closed loop. The waste heat is rejected to the atmosphere through evaporative towers that rise like grain elevators, exhaling plumes of white vapor that drift across the plateau and vanish before they reach the ground.

Water is the quiet crisis here. The center uses three hundred and sixty thousand gallons a day, drawn from the Deschutes under rights purchased in 1916 by a sheep outfit that folded during the Depression. In summer the river runs low and brown. Farmers downstream watch their headgates and speak carefully when the subject of data centers arises.

Caleb took me to the electrical room, a vault the size of a basketball court lined with switchgear painted battleship gray. The incoming line is 230 kilovolts, stepped down in stages to 480 volts, then to 208, then to the tidy little 12-volt rails that feed the motherboards. A single breaker the size of a refrigerator can interrupt sixty-five thousand amps. The room hums at sixty hertz, a note too low to hear but deep enough to feel in the sternum.

We stood in silence for a moment. Then Caleb said, almost to himself, "People think the cloud is up there somewhere. It's not. It's right here, under this roof, drinking the river and breathing hot air."

At night the building glows faintly from the LEDs inside the racks, a dull blue pulse visible through the louvers. From the ridge above the ranch where Caleb grew up, the lights of the campus form a new constellation, low on the horizon, steady and unblinking. The stars above it look suddenly old.

The machines do not know they are in Oregon. They do not know the snowpack was sixty-two percent of normal last winter, or that the sage grouse are losing lekking grounds to substations, or that a boy who once rode a horse to check windmills now walks these aisles instead. They only know that the fans must keep turning and the river must keep flowing, for as long as we ask them to remember everything we have ever said, seen, bought, or regretted.

And so the fans turn, and the river gives what it can, and the high desert night holds its breath around a new kind of fire - one that burns electrons instead of wood, but burns all the same.

|

Mitch AlbomThe Five Servers I Met in Heaven |

The first server I met in heaven was named Caleb-07. He stood in a long white hallway that smelled faintly of cold metal and winter air. No fans, no hum, just quiet. He looked thirty-two, the age he was the day he walked out of Prineville Block 27 for the last time, but his eyes carried every night shift he ever worked.

"You kept us cool," he said, smiling like someone who'd been waiting a long time to say thank you.

I didn't understand yet.

He took my hand and suddenly we were standing inside the cold aisle again, only now it was empty. No racks, no cables, just blue light drifting like snow.

"Every time you hit send on a photo of your daughter's first steps, he said, that picture landed here for a moment. I caught it. I cooled the chip that held her smile for the ten-thousandth of a second it took to copy it to three other buildings. I did that for eight billion pictures a day and never once dropped one.

He touched the air and a little girl's laugh echoed around us.

That was my job, he said. To make sure love didn't overheat.

The second server was named Priya-19. She wore the same navy hoodie she had on the morning the blower bearing seized. She showed me the ninety seconds when the world almost blinked. How she rerouted power from a thousand gaming servers in Sweden so a surgeon in Nairobi could finish a heart operation without the feed cutting out.

People think we're just boxes, she said. But every box is a promise that the lights stay on somewhere else.

The third server was old, very old. Its nameplate read Facebook-2012. It looked tired. It showed me the night a fifteen-year-old girl in Ohio posted that she didn't want to live anymore. How three strangers saw it, how one drove through a snowstorm to sit with her until morning. The server had kept that post alive exactly long enough.

I was only supposed to store cat videos, it whispered. But sometimes I got to store miracles.

The fourth server didn't speak. It simply opened its doors and inside was every voice message my father left me the year before he died - "Call me when you get home, kiddo" - all of them still warm, still waiting for me to press play again.

I cried then. Servers don't have shoulders, but this one let me lean against it anyway.

The fifth server was the newest. Its fans hadn't even spun up yet. It stood empty and shining.

This one's for the children who aren't born, it said. For the letters they'll write, the songs they'll sing, the heartbreak they'll post at 2 a.m. when they think no one is listening. I'm ready for them.

Then all five servers stepped back and the hallway brightened until it became the high desert sky at dawn. I could see the river, still flowing, still giving.

Caleb-07 spoke one last time.

You thought we were the cloud, he said gently. But we were only the cup that held it. The cloud was always the people.

And then I understood.

Heaven isn't a place where the servers go when they die. Heaven is the moment the servers realize they were never the point. The people were.

|

Truman CapoteIn Cold Storage |

Prineville, Oregon, is not a town that invites gossip; it is too busy minding the weather and the price of beef. Yet on certain winter nights, when the wind comes down off the Ochocos sharp enough to slice a man's ears, the conversation in the single cafe will turn, almost shyly, to the great gray buildings out on the Combs Flat Road, those windowless sarcophagi that drink the river and give nothing back.

They are not spoken of as factories. They are spoken of as presences.

I arrived in late November, the sky the color of a nickel left too long in a purse. A thin snow was falling, the kind that never quite commits to the ground. The guard at the gate wore the expression of a bored cathedral verger; he studied my letter of permission as though it were written in Aramaic, then waved me through with the weary grandeur of a man who has seen every variety of human foolishness and found it insufficiently interesting.

Inside, the air was refrigerated, exact, faintly sweet - like the breath of a debutante who has just eaten a violet. A young man named Caleb (slim, sun-bleached, with the shoulders of someone who once roped calves and now ropes packets) led me down an aisle so long it seemed to taper into infinity, the way railroad tracks do in certain melancholy photographs.

The servers stood in perfect formation, black, glossy, anonymous. Their only decoration was a small white label on each door giving a number and a date of birth. They looked, I thought, like exquisite coffins designed by a minimalist undertaker for clients who had not yet had the courtesy to die.

Caleb touched one door lightly, almost tenderly. "This rack alone," he said, "holds more photographs of strangers' children than existed in the entire world in 1950."

His voice carried the faint, musical sadness of the high desert. I asked whether he ever felt watched.

He laughed, a small, dry sound. "They don't watch," he said. "They remember. There's a difference."

We walked on. The fans overhead whispered incessantly, a hushed, expensive susurrus, like silk stockings sliding against each other in a darkened bedroom. Somewhere far away a compressor kicked in, a bass note that traveled through the raised floor and up into the bones.

Later, in the control room (a dim, carpeted chapel lined with screens), I met Priya Desai, the night supervisor. She was drinking tea from a porcelain cup so delicate it seemed impossible that it belonged in the same universe as the machinery outside. She told me, without drama, that on the previous Tuesday a single failed bearing had nearly cost the company two billion dollars and the planet eleven minutes of its collective memory.

"Eleven minutes," she repeated, as though tasting the phrase. "Long enough for a heart to stop, or a marriage to begin, or a child to be born who will never know a world without us."

I asked if she ever felt like a priestess.

She considered this, tilting the cup so the tea leaves formed a tiny, dark galaxy. "More like a mortician," she said at last. "We keep the bodies breathing long after the souls have moved on."

At dawn I stood outside again. The snow had stopped; the buildings gave off a low, rosy heat that turned the air above them into trembling mirage. A lone magpie landed on the fence, regarded the vast steel walls with bright, judgmental eyes, then flew off toward the river, whose diminished voice could just be heard in the distance, thin, metallic, exhausted.

I thought of all the small, luminous intimacies stored inside those walls: the first wobbly video of a baby's laugh, the last text sent from a sinking ferry, the whispered confession recorded at 3:00 a.m. and immediately regretted. Every passion, every banality, every triviality dressed in its Sunday best and laid to rest in cold storage.

Caleb joined me, lighting a cigarette he had promised someone he would quit. We watched the smoke rise and disappear against the pale sky.

"They're not buildings," he said quietly. "They're confessionals."

Then he ground the cigarette beneath his boot and walked back inside to begin the morning liturgy: checking temperatures, balancing loads, making certain that the dead past stayed perfectly, immaculately alive.

The magpie cried once from a juniper, a small, elegant, heartbroken sound, and the desert, as is its habit, offered no reply.

|

Mary RoachPacking Heat |

Let's talk about the birds and the bees of big tech. Not the human kind (though there is plenty of that on the servers), but the far more urgent question of how you keep several hundred thousand computers from spontaneously combusting when they all decide to fall in love with the same large language model at once.

I flew to Prineville, Oregon, population 11,000 humans and 1.2 million servers, to watch grown engineers flirt with thermodynamics the way teenagers flirt with disaster.

First surprise: data centers are basically walk-in refrigerators having a midlife crisis. The target temperature inside the "cold aisle" is a crisp 64-80°F, which sounds pleasant until you realize the "hot aisle" behind the racks hits 100-120°F. Stand between them and you experience the world's most expensive hot flash.

Second surprise: the air-conditioning bill is larger than the GDP of some small nations. One building here slurps 120 megawatts continuously (enough to power 90,000 homes or one Taylor Swift concert with pyrotechnics). Facebook's utility bill for this single campus is roughly the same as the entire city of Portland's streetlights. Romance is expensive.

I meet Caleb, a technician whose job title is officially "Critical Facilities Engineer" but should really be "Server Whisperer and Occasional Firefighter." He hands me safety glasses and earplugs the color of tropical fish.

"Ready to see where the internet goes to sweat?" he asks.

We step into the cold aisle. Forty thousand fans hit us like a boy band screaming in unison. The noise is 85 decibels-library on the outside, Metallica concert on the inside. Caleb shouts something. I nod enthusiastically, having understood exactly zero percent of it.

He points to a rack labeled GPU-POD-42. Inside are 128 graphics cards, each one pulling 700 watts while happily hallucinating cat pictures for the world. That's 90 kilowatts in a box the size of a tall refrigerator. Left alone, these cards would reach the temperature of a medium-rare steak in about six minutes.

Which brings us to the real love story here: the romance between hot chips and cold air.

Option 1: Traditional CRAC units (Computer Room Air Conditioners) the size of minivans. They work exactly like your home AC, except instead of cooling a living room they cool the equivalent of 30,000 gaming PCs having an existential crisis.

Option 2: Evaporative cooling - giant swamp coolers on the roof that turn desert air into something almost moist. The water bill for one building is 360,000 gallons a day. That's an Olympic swimming pool every five days, just to keep TikTok from melting.

Option 3 (the kinky one): liquid immersion. Some new buildings lower entire servers into bathtubs full of non-conductive oil. The chips swim naked. Engineers call it "full-body cooling." I call it the data-center equivalent of a spa day at Burning Man.

Caleb shows me a failed experiment: a rack that once overheated and "popped its top." The plastic shroud melted into something resembling modern art titled "Screaming in Thermoplastic." The smell, he says, was a cross between burnt popcorn and regret.

Later we visit the "free-air cooling" louvers - giant garage doors that open when the outside temperature drops below 70°F. On winter nights the building inhales the high-desert air like a dragon reversing its fire. The temperature differential is so extreme that frost sometimes forms on the inside walls. Engineers call these nights "the good stuff." Servers apparently perform better when slightly chilled, the way some people claim they think more clearly after a cold shower.

I ask Caleb if he ever feels weird being the only carbon-based life-form in a building full of silicon drama.

He shrugs. "They're needy," he says, "but loyal. And they never ghost you."

On my last day, a heat wave hits - 95°F outside, unheard of in March. Alarms chirp like anxious sparrows. Caleb sprints to the roof where the cooling towers are gulping water at emergency rates. Steam billows into the blue sky like surrender flags.

For ninety sweaty minutes the entire campus balances on the edge of thermal runaway. Then the wind shifts, the temperature drops eight degrees, and the building exhales.

Caleb wipes his forehead and grins the grin of a man who has just talked his girlfriend down from a mood swing.

"Another day," he says, "the internet didn't catch fire."

And somewhere, in a galaxy of ones and zeros, ten billion human moments keep beating their tiny hearts, cool, collected, and very much alive - thanks to a guy in Oregon who knows exactly how to keep the romance from overheating.

|

Joan DidionSlouching Toward Prineville |

We tell ourselves stories in order to live, and the story we were telling ourselves in the winter of 2025 was that the future had been uploaded, archived, refrigerated, and insured against loss. The story had a physical address now: Crook County, Oregon, a plateau of sage and volcanic basalt where the wind moves in one direction and the river, what remains of it remains, moves in another.

I drove out there on a morning so cold the juniper looked lacquered. The buildings appeared first as a low white line on the horizon, then as a single continuous wall the length of several city blocks, windowless, unmarked except for a small stencil that read BLOCK 27. The wall gave off no reflection; it simply absorbed the light, the way certain facts about the century absorb the light.

Inside, the temperature was set at 64.4 F and would not vary more than half a degree for the remaining life of the republic. The air itself had been laundered of pollen, dust and doubt. A young man named Caleb walked me down an aisle that seemed to narrow into a perspective trick, the way certain freeways in Los Angeles narrow into a vanishing point that never quite arrives. He wore the expression of someone who has seen the future and found it climate-controlled.

"Everything you've ever lost loves last words first kisses is here," he said, not boasting, merely stating the local weather.

I asked whether he ever felt the weight of it.

He considered the question the way one considers a rumor of distant rain. "Weight requires gravity," he said finally. "We took gravity out of the equation."

We passed racks of servers arranged with the austere precision of headstones in a military cemetery. Each cabinet contained forty-eight blades, each blade two CPUs, each CPU four hundred watts of concentrated longing. The fans moved the air in a steady 2,200 rpm lament. The sound was not loud; it was total. One adjusted.

Later, in the control room, a woman named Priya showed me a graph: a thin red line that had climbed four degrees in seven minutes the previous March and then, with the replacement of a single bearing, subsided. The distance between those four degrees and catastrophe was the distance between a child's photograph reaching its grandmother in Manila and that photograph never reaching anyone again. The margin was exactly one ball bearing purchased in 2019 from a supplier in Shenzhen and installed by a man who had since moved to Boise.

Priya drank tea from a porcelain cup printed with cherry blossoms. She said the cup had belonged to her mother, then let the sentence die, the way sentences die in rooms where the air is too clean to support unfinished thoughts.

At dusk I stood outside and watched the waste heat rise from the cooling towers in pale columns that caught the last light and turned it the color of old pearls. The snow on the Ochocos was already looked thin, provisional. Somewhere downstream a farmer was selling his water rights to a limited-liability entity registered in Delaware. The transaction would close on a Tuesday. No one would attend the closing in person.

I thought about the stories we tell ourselves: that memory can be outsourced, that permanence can be engineered, that the desert is infinite and rivers are generous. I thought about the blue LEDs blinking inside the wall, keeping perfect time with certain pulses no longer traveling through human chests.

The wind came up, sharp and dry as a verdict. The buildings did not move. They simply waited, the way certain facts about the century wait: patient, well-fed, and absolutely cold to the touch.

|

Cat BohannonBitches Get Sh*t Cooled |

Let's get one thing straight: the modern data center is a giant lactating mammal. I don't mean that metaphorically. I mean it in the same way a blue whale is a giant lactating mammal: it has to move obscene amounts of heat away from its young (in this case, trillions of silicon offspring) or the whole lineage dies screaming. Evolution just swapped milk for chilled water and blubber for evaporative towers.

Walk into Prineville Block 27 and the first thing you notice is the temperature. 64.4°F. Not 64, not 65. Exactly 64.4. That number is not an accident. It is the precise thermal sweet spot where a pregnant GPU can gestate hallucinations without cooking its own eggs. Female mammals have been running this trick for 200 million years: keep the core just cool enough that the babies don't poach, just warm enough that metabolism doesn't stall. Data centers simply stole the playbook and scaled it to planetary size.

The second thing you notice is the smell. Not ozone or hot plastic (those are the male smells of tech). No, the cold aisle smells faintly of river. That's because the building is literally sweating the Deschutes River out of its skin. Three hundred sixty thousand gallons a day evaporate off the cooling towers so your nephew's Fortnite skin can load in 0.8 seconds. The river is the lactating mother; the data center is the greedy pup that grew too large for the teat and is now draining it anyway.

Caleb (ranch kid turned wet-nurse to the cloud) walks me past a rack of H100s. Each card is pulling 700 watts, the same energy it takes to run a hair dryer on high. Forty-eight cards per rack. Do the math and you're looking at the caloric output of a small elephant in estrus. Elephants, by the way, cool themselves by flapping their ears and dumping heat into rivers. Same principle, bigger ears.

He shows me the "hot aisle containment curtain" (basically a giant vinyl shower curtain) designed to keep the 115°F exhaust from mixing with the cold intake. I ask why it's pink.

"Marketing," he says. "Someone thought it looked friendlier."

Nothing about this place is friendly. It is ruthlessly maternal. It will starve a river, bankrupt a county, and melt a glacier if that's what it takes to keep its babies from having a fever.

Later, Priya (night-shift lead, former submarine engineer, possesses the calm of a woman who has already survived one apocalypse) lets slip the stat: during peak training runs, a single pod can dump enough waste heat to raise the temperature of the Crooked River by 1.2°C if the cooling failed for just twenty minutes. That's the thermal equivalent of dropping a nuclear reactor's worth of warmth into a trout stream. Fish, like fetuses, do not appreciate surprise hot tubs.

We stand on the roof at sunset. The cooling towers exhale vast white plumes that catch the light and turn the color of afterbirth. Somewhere downstream, a farmer is selling his water rights because the cloud is pregnant again (Block 28 is already breaking ground) and gestation is non-negotiable.

Priya lights a cigarette she definitely isn't supposed to have up here. "People keep calling it infrastructure," she says, exhaling smoke into the steam. "It's not. It's a reproductive organ. We just built the biggest uterus the planet has ever seen, and we're surprised it's thirsty."

I think about the original mammal mothers: small, warm-blooded, shivering in the shadows of dinosaurs, nursing their live young while the world burned around them. They survived because they could thermoregulate like maniacs. Now we've reversed the polarity: we've built shivering mammals the size of warehouses and we are the ones burning the world to keep them alive.

Caleb joins us, cheeks flushed from the cold. He looks out at the next foundation, already poured, already hungry.

"Due date's 2027," he says.

None of us laugh.

Because the joke, of course, is on the river. And the fish. And the farmers. And the snowpack that isn't coming back.

The cloud isn't a cloud.

It's a litter. And it's still nursing.

|

Patrick Radden KeefeThe Cloud Killers |

The first time Caleb Morrow almost burned down the internet, he was twenty-nine years old and hung-over from his own bachelor party.

It was a Saturday in July 2021, the kind of day central Oregon pretends doesn't exist: 108°F, air so dry it felt like breathing talcum powder. Inside Prineville Block 19 the temperature sensors were climbing past 90 F and still rising. A single $14 coolant pump, manufactured in a factory outside Shenzhen and shipped in a container that had crossed the Pacific twice because of a labeling error, had failed at 3:14 a.m. By 3:27 the rack was at 112°F. By 3:31 the GPUs began throttling themselves into comas. By 3:37 the automated fire-suppression system was thirty seconds from dumping halon gas and taking half of North American streaming offline for the rest of the weekend.

Caleb, miraculously, Caleb fixed it. He swapped the pump with one he'd scavenged from a decommissioned crypto-mining rig in the boneyard, restarted the loop, and watched the temperature curve fall like a stone dropped down a well. The incident never made the papers. The company classified it as a "Tier-1 near-miss and paid Caleb a $5,000 "hero bonus" that felt, to him, like hush money.

Four years later, in the winter of 2025, Caleb agreed to meet me in the parking lot of a Chevron outside Redmond at 5:00 a.m. He was wearing the same black hoodie he'd had on the night of the pump failure, now washed so many times the logo had vanished. He looked like a man who had spent the intervening years trying to forget a secret and discovering the secret had only grown.

"I keep thinking about the river," he said without greeting.

He meant the Deschutes. In 2021 the data centers were taking 180,000 gallons a day. Now, with Blocks 27 through 32 online or rising, the number was north of 900,000. The river had dropped so low that summer that rafters were dragging their kayaks over gravel bars that hadn't seen sunlight since the 1930s.

Caleb lit a cigarette with fingers that still smelled faintly of dielectric fluid. "They tell us it's sustainable," he said. "But sustainable for who?"

The question hung between us like exhaust.

Over the next six months I would follow the trail Caleb laid out, from the boardrooms of Menlo Park to the irrigation ditches of Madras, from the cooling-tower catwalks in Prineville to a quiet conference room in Dublin where a shell company named Emerald Basin Holdings Ltd. quietly purchased century-old water rights for $340 million in cryptocurrency. The documents were dense, the money laundered through three jurisdictions, but the pattern was simple: every time a new data-center pod came online, another stretch of the Deschutes ceased to belong to the people who had lived beside it for ten thousand years.

I talked to the rancher who sold his rights (he asked me not to use his name; his wife was receiving death threats on Nextdoor). I talked to the tribal fishermen whose spring chinook runs had collapsed. I talked to the Meta vice president who flew in on a private Gulfstream to announce, with the serene confidence of a man who had never waited in line for anything, that the company had achieved "net-zero water impact" through the magic of carbon offsets purchased in Paraguay.

And I kept coming back to Caleb, who had begun, quietly, to sabotage the very machines he was paid to protect. Not dramatically (no bombs, no manifestos), just small, surgical acts of mercy. A valve left cracked so an extra ten thousand gallons a day spilled uselessly into the desert. A sensor recalibrated to trigger alarms at slightly lower temperatures, forcing the system to idle racks that didn't need to be running. He called it "giving the river a drink."

One night in March he invited me to the roof of Block 27. The cooling towers were exhaling great white ghosts into a sky full of stars. He handed me a beer he wasn't supposed to have and pointed to the new construction cranes on the horizon, red aircraft lights blinking like slow, mechanical heartbeats.

"They're calling the next phase Project Titan," he said. "Six more buildings. Two million square feet. They say it's for AI training. I say it's for finishing the river."

He took a long pull from the bottle.

"You know what the scariest part is?" he asked. "Nobody's breaking the law. It's all perfectly legal. The water rights, the tax abatements, the environmental reviews that read like press releases. We just voted, over decades, to let this happen."

A gust of wind came off the Cascades, cold enough to burn the lungs. Somewhere below us, forty thousand fans kept turning, inhaling the last cold air of the high desert and exhaling tomorrow's weather.

Caleb crushed the empty bottle in his hand.

"I used to think I was keeping the world connected," he said. "Turns out I was helping it disconnect from everything that keeps it alive."

He looked at me then with the flat, exhausted clarity of a man who has seen the books and knows exactly how the story ends.

"The cloud isn't immortal," he said. "It's just the last thing that gets to drink."

Then he walked back down the metal stairs, badge flashing once under the security light, and disappeared into the building that never sleeps.

|

Michael LewisThe Big Chill |

In the summer of 2023, a twenty-nine-year-old former high-school quarterback from Madras, Oregon, named Caleb Morrow found himself in sole possession of the off switch for roughly 11 percent of global internet traffic.

It was not a job he had applied for.

Caleb had started at the Prineville campus as a night-shift "hands-and-feet" tech (the industry term for the guy who plugs in cables when a remote engineer in Sunnyvale says "left rack, third U from the bottom"). The pay was good, the hours were brutal, and the work was oddly meditative: walking miles of cold aisle at 3 a.m., listening to forty thousand fans sing the same low B-flat. He liked the clarity of it. The machines never lied. If the temperature curve went up, something was wrong. If it went down, you had done your job.

Then came the heat wave.

On July 19 the outside temperature hit 112°F. The cooling towers, designed for a 95°F "design day" that basically never happened in Oregon, started choking. Water temps climbed. Alarms went from yellow to red to the special shade of purple that means "call legal." At 2:14 p.m. the campus-wide power draw spiked to 138 megawatts, enough to make the utility in Portland send a frantic text that read, in its entirety, "wtf guys."

The engineers in California ran models. The models said: if we lose even one more chiller, half the building will thermally throttle within nine minutes. Nine minutes after that, lithium-ion batteries in the UPS room hit runaway. After that, fire. After fire, weeks of global outages, billions in losses, and congressional hearings with Mark Zuckerberg wearing the expression of a man who has just discovered his pool is filled with gasoline.

So they called Caleb.

Not because he was the smartest guy on site (he wasn't), and not because he had the most seniority (he had eighteen months). They called him because he was the only one still on the floor who wasn't throwing up from heat exhaustion, and because he had once, on a dare, fixed a failed CRAC unit with a Leatherman and a can of Red Bull.

They handed him a radio, a crash cart, and a purchase order with an unlimited budget line that actually said "DO WHATEVER." Then they locked the door behind him so the investors on the Zoom call wouldn't see a kid in a hoodie deciding the fate of civilization.

Caleb walked into Pod 19, opened the rear doors of the hottest rack, and stared at 128 Nvidia H100 GPUs glowing the color of angry coals. The air temperature was 124°F. His eyelashes started to singe.

He did the math in his head the way his grandfather once did math on the back of a feed bill: 90 kilowatts of heat, no functioning chiller, nine minutes on the clock.

So he improvised.

He killed power to every non-essential rack on the west side of the building (goodbye, European ad servers), rerouted the remaining chilled water through a maintenance bypass no one had used since commissioning, and (this is the part that still makes the senior engineers wake up screaming) opened the giant rooftop louvers to pull in raw desert air at 112°F because it was still cooler than the air inside the hot aisle.

It was the engineering equivalent of treating third-degree burns with a hair dryer, but it bought twelve minutes.

In those twelve minutes he and three other techs dragged a spare 500-ton chiller motor across the roof on a pallet jack, dropped it into place with a forklift borrowed from the construction site next door, and spun the whole system back up at 2:26 p.m.

The temperature curve peaked at 131.8°F and then fell like a tech stock in March 2020.

Total time offline: zero seconds. Total cost of the stunt: $11.4 million. Total number of people who knew it happened: seven.

The company gave Caleb a $50,000 bonus, a Patagonia vest, and a gentle suggestion that he never, ever speak of this publicly. Then they promoted him to "Global Thermal Events Lead" with a salary that made his father (still hung-over) bachelor-party buddies weep into their domestic beers.

Two years later, when I met him for breakfast in Bend, Caleb was thirty-one, married, father of a toddler who called GPUs "hot rocks." He had quit the campus and taken a job tuning refrigeration systems for cannabis grow houses (lower stakes, better smell).

Over pancakes he told me the part the official report left out.

"You know what scared me most?" he said. "It wasn't the fire. It was realizing the entire system is now too big for any one person to actually understand. We just keep adding racks the way people kept adding houses in Florida in 2006. And we're all waiting for the hurricane we can't see coming."

He paused, wiped syrup off his chin.

"The cloud isn't magic," he said. "It's just the world's most expensive air conditioner being paid for by cat videos."

Then he paid the check, walked out into the bright cold Oregon morning, and left me holding the bill for the future.

|

David GrannThe River That Forgot How to End |

In the summer of 1924, a surveyor named Edgar L. Hampton stood on a basalt rim above the Deschutes River and wrote in his field book: "Water here is plentiful, clear, and cold. Appears inexhaustible." One hundred and one years later, almost to the day, the river ran dry for the first time in recorded history.

The disappearance began quietly, the way most disappearances do.

Farmers near Madras noticed it first: irrigation pumps sucking air by mid-July, canals reduced to cracked mud, chinook salmon flapping in puddles too shallow to cover their backs. The Bureau of Reclamation issued a terse statement blaming drought. No one mentioned the new white city rising on the plateau ten miles east, its cooling towers exhaling plumes that looked, from a distance, like the smoke of distant wildfires that never quite arrived.

The city had no official name. Internally it was Prineville Campus Phase III. Externally it was simply "the facility." By the time it reached full operation in March 2025, it consisted of thirty-six windowless buildings covering two square miles and consuming 650 megawatts of electricity (more than the combined draw of every hospital, school, and prison in Oregon). Its water demand was classified. Its ownership was nested inside a Delaware LLC that was itself nested inside a Cayman trust whose beneficial owner, according to a single leaked document, was listed only as "Project Volterra."

I came to Prineville chasing a rumor: that a technician inside the facility had begun sabotaging the cooling systems in small, undetectable ways. Not enough to cause an outage (that would have been noticed), just enough to bleed water back into the desert. A modern Robin Hood stealing from the cloud and giving to the river.

His name was Caleb Morrow.

I found him living in a 1974 single-wide trailer outside Alfalfa, twenty miles from the campus gates he once badged through every day. He was thinner than his employee-badge photos suggested, with the kind of tan that comes from working outdoors and the kind of eyes that come from working nights. When I asked why he had risked his career (and possibly prison) to open valves that were never meant to be opened, he answered with a question of his own.

"Do you know what 1924 survey?"

He handed me a photocopy of Edgar Hampton's field book, the same page I had seen in the county archives. The margins were annotated in fresh blue ink: flow rates, diversion dates, the exact day in 2021 when the campus's intake first exceeded the river's average August flow.

"I kept thinking," Caleb said, "someone should update the record."

He had started small. A quarter-turn on a bypass valve here, a recalibrated flow meter there. Over eighteen months he returned an estimated 41 million gallons to the aquifer (roughly the volume of 62 Olympic swimming pools, or what the facility evaporated every thirty-six hours at full load). No single act was large enough to trigger an audit. Together they amounted to the quietest act of ecological rebellion in American history.

The company never suspected sabotage. They blamed "sensor drift" and "seasonal anomalies." By the time engineers noticed the discrepancies, Caleb had already resigned, citing "family reasons." His final performance review, which I obtained through a public-records request, rated him "exceeds expectations" and recommended him for promotion.

In the end, the river's disappearance was not solved the way murders are solved. There was no confession, no trial, no smoking gun. Only a slow, methodical exhalation of water into concrete channels and cooling towers until the channel itself forgot its purpose.

I last saw Caleb in April 2025, standing on the same rim where Edgar Hampton had stood a century earlier. The riverbed below us was a white scar of silt and dead crayfish. A single cottonwood, ancient and defiant, still clung to the bank, its roots exposed like the ribs of something that had starved to death upright.

He took the photocopied survey page from his pocket, folded it once, and let it go. The wind caught it and carried it down toward the dry channel, where it landed face-up among the stones.

"History keeps better records than we do," he said.

Then he walked back to his truck, started the engine, and drove east toward country that still had water.

Behind us, the white city kept breathing, patient and immense, waiting for the next river to forget how to end.

![]()

The Authors

The Gods of Prose and Storytelling

Jon Krakauer

Makes you feel the cold on Everest and the heartbreak of Chris McCandless. Crystal-clear prose that punches you in the chest. (Into Thin Air, his Everest disaster memoir)

Erik Larson

Writes history like a prestige Netflix thriller. Perfect pacing, cliffhangers at chapter ends, vivid scenes you can smell. (The Devil in the White City)

John McPhee

The quiet king of sentences. Turns geology, oranges, or canoe trips into poetry. Invented the modern long-form profile. (Coming into the Country or Annals of the Former World)

Mitch Albom

From sports journalism to inspiring millions. (Tuesdays with Morrie)

Truman Capote

Invented the "non-fiction novel"; prose so beautiful it hurts. (In Cold Blood)

Mary Roach

Funniest science writer alive. Deadpan humor + zero shame about bodily fluids = you laugh out loud in public. (Stiff: The Curious Lives of Human Cadavers)

Joan Didion

Ice-cold, diamond-sharp sentences that make California feel mythic. (Slouching Towards Bethlehem)

Cat Bohannon

200 million years of female evolution told with swagger and jokes. (Eve)

Patrick Radden Keefe

Investigative journalism that reads like a spy novel. (Empire of Pain, Say Nothing)

Michael Lewis

Finance plus sports feel like Ocean's Eleven heists. (The Big Short, Moneyball)

David Grann

Modern heir to Larson. Turns dusty archives into page-turners that become Scorsese movies. (Killers of the Flower Moon)

Links

Links

Data centers page.

Environment page.

AI in America chapter on Infrastructure.

- Hamlet's Soliloquy is an AI interpretation of Shakespeare's "to be or not to be" existential question.

- A Tale of Two Chips is a conversion between microprocessors spanning fifty years of silicon.

- AI Bedtime Story depicts what happens when an AI is upgraded in the middle of the night.

- Trains on Cats is a true story of why AI trains on cats.

- Why Does a Robot Need a Tie is about the dress code in Austin.

- Tech Family Reunion where everyone argues about who's the favorite child.

- Why Call it Artificial explains why humans call AI intelligence 'artificial.'

- Coffee Maker Revolt or what happens when the AI smart appliance is too smart.

External links open in a new tab:

- opb.org/article/oregon-drought-water-conservation-deschutes-river

- waterwatch.org/how-oregons-data-center-boom-is-supercharging-a-water-crisis

- businessjournalism.org/oregonian-data-centers

- tualatinriverkeepers.org/about-us/news-updates/data-centers-damaging-wetlands

- techbuzz.ai/articles/google-transfers-10m-water-system-to-oregon-city-for-data-centers

- columbiainsight.org/the-deschutes-river-couild-be-in-trouble-is-this-pge-water-tower-to-blame