The Rise of Machine Learning and Neural Networks

The Rise of Machine Learning and Neural Networks

Artificial Intelligence in America has always evolved in waves, with periods of explosive discovery followed by long winters of disappointment. But no wave transformed the world more profoundly than the rise of machine learning and deep neural networks starting in the 1980s. What began as an obscure branch of cognitive science in the mid-20th century became the beating heart of the digital economy. And the United States, through its universities, tech giants, and start-up culture, stood at the center of that transformation.

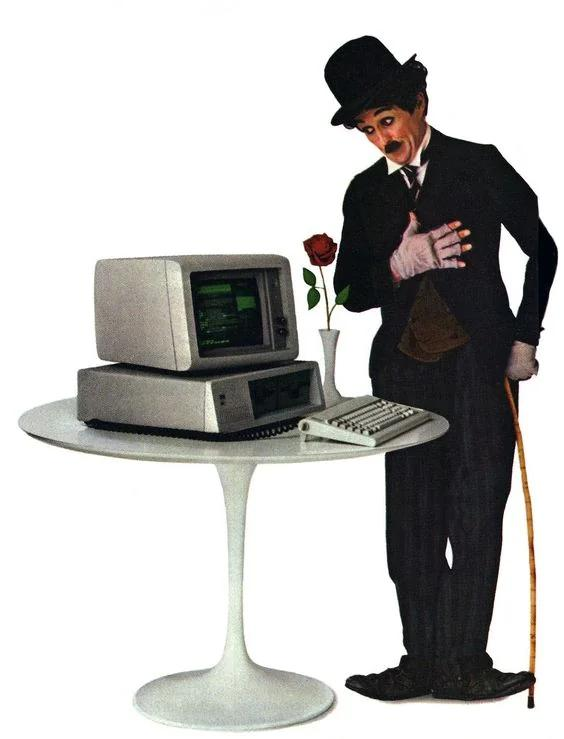

The single most influential computer ever built was introduced on August 12, 1981, when IBM revealed the IBM PC to the press and the world. At a grand event in a New York City hotel, journalists were given the opportunity to test it out while Project Manager Don Estridge and others stood by, available for questions. Estridge confirmed it would go on sale at Sears and ComputerLand stores from August 15 onward. The coverage the next day was overwhelmingly positive. The machine was quick, reliable, and well built. The software was good and the price point didn't break the bank. The press had already fallen in love with the PC, a viable contender to the Apple II for small businesses. That same year, for the first time in its history, Time Magazine didn't declare a "Man of the Year." The magazine declared it a "Machine of the Year." The PC had conquered the world.

"I think we're in an era where the public has adopted computing the same way it adopted the automobile." Estridge told Byte Magazine two years later.

The 1980s represented a unique period in computing, featuring radical advancements in hardware components that made systems faster, smaller, cheaper, and far more capable than their predecessors. In semiconductors, the central processing unit (CPU) saw exponential growth in complexity and speed, thanks largely to advancements in Very Large Scale Integration (VLSI), the process of creating microchips with hundreds of thousands of transistors. The IBM PC was introduced with an 8-bit processor; by the middle of the decade, 32-bit processors were being produced by Intel, enabling modern operating systems and multitasking.

Like personal computing, AI was a beneficiary of these advancements. Specialized AI hardware flourished. Machine learning's resurgence was aided by the improved hardware. There were faster microprocessors, cheaper memory, specialized research computers (e.g., Connection Machine), increased availability of workstations for universities, and emerging parallel computing paradigms. America's computer science departments suddenly had the tools to test learning algorithms at scale, making research practical rather than purely theoretical. And after years of skepticism, U.S. agencies cautiously returned to AI investment.

Teaching Machines to Learn

Imagine trying to write a computer program that can recognize whether a photo contains a cat. You'd need to tell the computer exactly what to look for: pointy ears, whiskers, four legs, fur, certain eye shapes, and so on. But cats come in so many varieties--different colors, sizes, positions, lighting conditions--that writing explicit rules for every possibility would be nearly impossible. You'd end up with thousands of "if-then" statements, and your program would still fail constantly.

Now imagine a different approach: instead of telling the computer the rules, you show it 10,000 photos labeled "cat" and 10,000 labeled "not cat," and the computer figures out the patterns itself. It learns what features distinguish cats from everything else. This is machine learning: getting computers to learn from examples rather than following explicit programming.

And when we structure that learning process using artificial "neurons" inspired by the brain, connected in layers that process information in increasingly sophisticated ways, we're using neural networks, the technology that powers much of today's AI, from facial recognition to language translation to self-driving cars.

This chapter presents a journey through the history of these revolutionary technologies. We'll learn about the brilliant scientists who pioneered these ideas, the "winters" when the field of AI nearly died, the unexpected breakthroughs that revived it, and the explosion of progress in recent years that's transforming society across the globe.

Understanding this history matters because machine learning and neural networks are reshaping our world. They influence what we see on social media, how our search results appear, whether loan applications are approved, how doctors diagnose diseases, and increasingly, how decisions are made about everything from hiring to criminal justice. By understanding where these technologies came from and how they evolved, we'll better understand both their power and their limitations.

When People First Dreamed of Thinking Machines

The story begins in the 1940s, when the first electronic computers were being built. These early machines were massive room-sized contraptions with vacuum tubes instead of transistors. They were created primarily for military use during World War II to calculate artillery trajectories and break enemy codes.

The most influential figure was Alan Turing, a British mathematician who defined what computers could theoretically do and imagined machines that could think. In 1950, he proposed the famous "Turing Test": if a machine could converse with you in a way indistinguishable from a human, could we say it was intelligent?

In America, pioneers like John von Neumann at Princeton designed a computer architecture that's still used today (the "von Neumann architecture") where programs and data share the same memory. These early computer scientists started wondering: if we can build machines that calculate, could we build machines that think?

The McCulloch-Pitts Neuron: The First Artificial Neuron

The first mathematical model of how a neuron might work came from an unlikely collaboration between Warren McCulloch (a neurophysiologist at MIT) and Walter Pitts (a brilliant young mathematician). In 1943, they published "A Logical Calculus of the Ideas Immanent in Nervous Activity," a paper with an intimidating title but a simple core idea. They proposed that neurons could be modeled as simple logic gates. A biological neuron:

1. Receives signals from other neurons

2. Adds

them up

3. If the total exceeds a threshold, it "fires" and sends a

signal onward

McCulloch and Pitts showed we could build any logical function (AND, OR, NOT) using networks of these simple artificial neurons. This was revolutionary: it suggested the brain itself might be a computer, and that we might be able to build artificial brains.

Their work had a profound insight: complex intelligence might emerge from simple components connected in the right ways. This idea would inspire decades of research, though it would take many years to figure out how to actually build useful neural networks.

Arthur Samuel's Checkers Program

Arthur Samuel at IBM created one of the first successful machine learning programs. His checkers program didn't just follow programmed strategies, it learned by playing thousands of games against itself, discovering which board positions were advantageous. By 1962, it could beat a Connecticut state champion.

Samuel coined the term "machine learning" and demonstrated that computers could improve through experience. His approach was revolutionary though limited to the specific domain of checkers.

The First Learning Neural Network

Frank Rosenblatt, a psychologist at Cornell, built something more ambitious: the Perceptron, the first artificial neural network that could actually learn.

Imagine a simple artificial neuron that takes several inputs, multiplies each by a "weight," adds them up, and produces an output (either 0 or 1, like "yes" or "no"). The Perceptron could learn what weights to use by seeing examples:

-

Show it many examples of inputs and correct outputs

-

When it makes a mistake, adjust the weights slightly

-

Repeat until it learns the pattern

Rosenblatt built a physical machine called the Mark I Perceptron; a room-sized device with 400 photocells representing inputs, connected to a simple artificial neuron. He trained it to recognize simple shapes and patterns.

The U.S. Navy was so impressed they funded research, hoping to use Perceptrons for image recognition. The media went wild with excitement. The New York Times ran a story predicting Perceptrons would "be able to walk, talk, see, write, reproduce itself and be conscious of its existence." This was the first neural network hype cycle, but it wouldn't be the last.

The First AI Winter: When the Dream Nearly Died

Despite the hype, Rosenblatt's Perceptron had a fundamental limitation that would nearly kill neural network research for decades. In 1969, Marvin Minsky and Seymour Papert (both at MIT) published a book called Perceptrons, which mathematically proved that simple perceptrons could only solve "linearly separable" problems; that is, problems where you can draw a straight line separating the categories.

The famous example they used was XOR (exclusive or):

If input A is on OR input B is on (but not both),

output 1

Otherwise, output 0

A simple perceptron couldn't learn this pattern no matter how many examples you showed it. The problem required a curved boundary, and perceptrons could only create straight ones. Now, Minsky and Papert knew that multiple layers of perceptrons could solve XOR. But they argued that:

1. We didn't have good methods to train multi-layer

networks

2. The computational power required seemed impractical

3.

There were theoretical reasons to doubt multi-layer networks would work well

Their book was mathematically brilliant though devastating for the fledgling AI industry. Funding for neural network research largely dried up. The field entered what's now called the First AI Winter, a period when AI research generally, and neural networks specifically, fell out of favor.

Several factors combined to cause this to happen:

-

Overpromising and Underdelivering: Early AI researchers had promised too much too soon. They predicted machines would match human intelligence within a decade or two. When this didn't happen, disappointment set in. Funding agencies and the public felt misled.

-

Limited Computing Power: The computers of the 1960s-70s were primitive by today's standards. What we now do on smartphones required room-sized machines costing millions. Training complex neural networks was computationally infeasible.

-

Limited Data: Machine learning requires lots of examples. In the pre-internet era, gathering large datasets was difficult and expensive. Without big data, learning algorithms couldn't learn much.

-

Alternative Approaches Seemed More Promising: Symbolic AI (teaching computers to manipulate symbols and follow logical rules) seemed more successful in the short term. Systems that could prove mathematical theorems or solve algebra problems were more impressive than neural networks that could barely learn XOR.

-

Cultural Factors: There was also an element of academic politics. Minsky and Papert were leading figures in AI, and their skepticism about neural networks influenced funding and research directions. Some neural network researchers felt their approach was unfairly dismissed.

Through the 1970s, neural network research nearly stopped in America. Most AI researchers worked on symbolic systems. A few lonely researchers kept working on learning algorithms and neural networks, but they were marginalized in the field.

This period teaches an important lesson: scientific progress isn't smooth and inevitable. Sometimes promising approaches get abandoned, not because they're wrong, but because of circumstances like limited technology, academic politics, funding priorities, or just bad timing.

Important Ideas Developed in Obscurity

While neural networks were out of fashion, some researchers quietly made crucial advances that would later prove essential. Remember how Minsky and Papert said we couldn't train multi-layer neural networks? They were wrong; science just hadn't figured out how yet. The solution was an algorithm called backpropagation ("backward propagation of errors"). While the basic idea had been discovered multiple times by different researchers in different fields, the key paper for machine learning came in 1986 from David Rumelhart, Geoffrey Hinton (then at Carnegie Mellon), and Ronald Williams.

Here's the basic idea in non-technical terms: Imagine you're training a multi-layer neural network to recognize handwritten digits. You show it a picture of a "3" and it incorrectly says "8." How do you know which parts of the network to adjust? Backpropagation works backward through the network:

1. Start at the output: "You said 8 but it should be

3. That's wrong."

2. Work backward through the layers: "You made this

mistake because the layer before you was sending these signals..."

3.

Keep going backward through all layers, figuring out how each contributed to

the error

4. Adjust all the weights throughout the network to reduce the

error

This solved the multi-layer training problem. Now you

could train "deep" networks with many layers; hence the term "deep learning"

that would become popular decades later.

But here's the interesting part:

backpropagation was published in 1986, but it didn't immediately

revolutionize the field. Why not? Computers were still too slow. Training

neural networks with backpropagation requires massive computation. The

computers of the 1980s couldn't handle it. And there still wasn't much data

available for training. So backpropagation was important, but it was ahead

of its time. The pieces were coming together, but not yet assembled.

Convolutional Neural Networks: Inspired by Vision

Yann LeCun, a French researcher working at AT&T Bell Labs in New Jersey, developed an important innovation called convolutional neural networks (CNNs). LeCun was inspired by how the visual cortex in the brain processes images. In your brain, early neurons respond to simple features like edges at particular angles. These feed into neurons that recognize combinations of edges, which feed into neurons recognizing more complex shapes, and so on. Visual processing is hierarchical, where simple features combine into complex ones.

LeCun designed neural networks that worked similarly:

-

Early layers detect simple patterns (edges, textures)

-

Middle layers combine these into more complex patterns (shapes, parts)

-

Later layers recognize whole objects

His networks also used "convolution." The same basic pattern-detector slides across different parts of the image, so the network doesn't have to learn separately what a vertical edge looks like in the top-left versus the bottom-right. In 1989, LeCun demonstrated a CNN that could read handwritten zip codes. AT&T deployed his system to automatically read millions of checks in banks. This was one of the first commercially successful applications of neural networks. But CNNs were still limited. They worked for simple tasks like reading digits but couldn't handle complex images. Computing power remained a bottleneck.

Support Vector Machines and Other Approaches

Through the 1990s, neural networks competed with other machine learning approaches. Vladimir Vapnik at AT&T Bell Labs, a hotbed of machine learning research, developed Support Vector Machines (SVMs), elegant mathematical approaches to a classification that worked well with limited data. For much of the 1990s, SVMs and similar techniques actually outperformed neural networks on many tasks. Neural networks were just one approach among many, and not necessarily the best one.

The Second AI Winter and the Rise of Statistical Learning

In the late 1980s and early 1990s, AI faced another crisis. Expert systems (programs encoding human expertise in narrow domains) had been commercially successful in the 1980s but proved brittle and hard to maintain. When the expert system boom collapsed, it took down much of the AI industry with it.

This Second AI Winter was actually less severe for machine learning than the first. Machine learning was quietly growing more practical and finding applications, although it was low-profile. The term "artificial intelligence" became somewhat embarrassing so researchers talked about "machine learning" or "statistical learning" instead.

While neural networks remained limited, machine learning generally was becoming more successful through the 1990s. Here's why:

-

Decision Trees and Random Forests: Methods that make decisions by asking a series of yes/no questions proved useful for many applications.

-

Spam Filtering: Email spam filters using machine learning became widespread.

-

Recommendation Systems: Amazon and Netflix began using machine learning to recommend products and movies.

-

Web Search: Google's PageRank algorithm, while not traditional machine learning, showed how mathematical approaches could create enormous value from data.

Machine learning was becoming embedded in everyday tech, even if people didn't realize it. Neural networks, though, remained a niche interest. It was viewed as one approach among many, not clearly superior.

The Deep Learning Revolution: When Everything Changed

Geoffrey Hinton, a British-Canadian researcher who had been working on neural networks since the 1980s (including co-inventing backpropagation), published papers in 2006 showing how to train very deep neural networks (networks with many layers).

The problem with deep networks had been that backpropagation didn't work well in very deep networks. When errors are propagated backward through many layers, the signal gets weaker and weaker (the "vanishing gradient problem"), so the early layers don't learn effectively. Hinton developed techniques to get around this problem:

-

Pre-training layers one at a time before training the whole network

-

Using specific architectures (like "restricted Boltzmann machines") that worked better

-

Mathematical tricks that helped gradients flow through deep networks

His work showed that deep learning could actually work. Deeper networks could learn more complex patterns than shallow ones. But even Hinton's breakthrough didn't immediately transform the field. The real deep learning revolution came from a combination of three factors that came together around 2012:

1. Big Data

The internet had created massive datasets. There were millions of labeled images from photo-sharing sites, huge text corpora from websites and books, millions of videos on YouTube, and billions of interactions on social media. For the first time, researchers had enough data to train really large neural networks. Machine learning had always been data-hungry, and now there was finally enough food to feed it.

2. Graphics Processing Units (GPUs)

Video game graphics cards, designed to render complex 3D scenes, turned out to be perfect for neural network training. GPUs contain thousands of simple processors that can do many calculations simultaneously, exactly what neural network training requires. Researchers discovered that training neural networks on GPUs could be 10-100 times faster than on regular CPUs. What took weeks now took days or hours. This was a game-changer. The irony is beautiful: technology developed for entertainment (gaming) enabled breakthroughs in AI. And NVIDIA was the biggest winner of all.

3. Better Algorithms and Techniques

Researchers developed numerous improvements to neural network training:

-

ReLU activation functions (simpler math that works better)

-

Dropout (randomly disabling parts of the network during training to prevent overfitting)

-

Batch normalization (normalizing signals between layers)

-

Better optimization algorithms

-

Data augmentation (artificially expanding datasets by modifying images)

Each improvement was modest, but together they made deep learning much more practical and powerful./p>

The ImageNet Moment: The Revolution Becomes Visible

Every year since 2010, researchers competed in the ImageNet Challenge. The object is to train a system to recognize objects in a million images across 1,000 categories (dogs, cats, vehicles, foods, etc.). It serves as a standard benchmark for evaluating the performance of deep learning models. This was extraordinarily difficult, a feat far beyond what computers could do well. In 2012, Alex Krizhevsky, Ilya Sutskever, and Geoffrey Hinton (at the University of Toronto) entered a deep convolutional neural network they called "AlexNet." It used:

-

GPUs for training (training took a week on two gaming GPUs)

-

The techniques Hinton had been developing

-

Clever tricks and lots of data

AlexNet crushed the competition. It achieved a 15.3% error rate, while the second-place system (using traditional computer vision methods) got a 26.2% error rate. This was a huge, shocking improvement.

The ImageNet 2012 result is now recognized as the moment when deep learning "won." Within a year or two major tech companies hired deep learning researchers or acquired their startups. Research funding flooded into deep learning. Computer science students rushed to take machine learning courses. The number of deep learning research papers exploded. What had been a niche approach suddenly became the hottest thing in AI.

Unlike the Perceptron hype in the 1960s, the deep learning revolution had substance:

It Actually Worked: Deep learning systems achieved superhuman performance on specific tasks. It wasvbetter than expert humans at recognizing objects in images, playing games, and other challenges.

It Kept Improving: Unlike previous AI approaches that plateaued, deep learning kept getting better as you added more data, more computing, and larger networks. There was no obvious ceiling.

It Was General: The same basic architecture (convolutional neural networks) could be trained to recognize faces, read text, analyze medical images, play video games, and much more. This suggested real progress toward general-purpose AI.

It Had Commercial Value: Companies could immediately deploy deep learning for valuable applications like image search, speech recognition, translation, recommendations, and more.

The Explosion of Progress

Since 2012, progress has been breathtakingly rapid. Here are some of the major developments:

Computer Vision Breakthroughs

Facial Recognition: By the mid-2010s, deep learning systems achieved human-level (and then superhuman) performance at recognizing faces. This technology is now ubiquitous. Examples include unlocking smartphones, tagging photos, airport security, and surveillance.

Object Detection: Systems can now identify and locate multiple objects in complex scenes in real-time, which is critical for self-driving cars and robotics.

Medical Imaging: Neural networks can detect cancers, analyze X-rays and MRIs, and identify diseases from scans, sometimes surpassing human radiologists in accuracy.

Deepfakes: For better or worse, neural networks can now generate highly realistic fake images and videos, a technology with both creative applications and serious misinformation risks.

Speech and Language

Speech Recognition (2016-): Deep learning revolutionized speech recognition. Systems like Siri, Alexa, and Google Assistant use deep neural networks to understand spoken language with accuracy that seemed impossible just a few years earlier.

Machine Translation (2016): Google switched to neural network-based translation and saw dramatic quality improvements. Neural translation is now standard.

Language Models (2018-Present): This is perhaps the most dramatic recent development. Large neural networks trained on massive text data can write coherent text, answer questions, summarize documents, write code, and more. Key developments:

-

Word2Vec (2013): Method for representing words as vectors, capturing semantic relationships

-

Transformers (2017): A new neural network architecture (from Google researchers) that processed text more effectively than previous approaches

-

BERT (2018, Google): Pre-trained language model that understood context bidirectionally

-

GPT-2 (2019, OpenAI): Language model so good at generating coherent text that OpenAI initially didn't release it fully, fearing misuse

-

GPT-3 (2020, OpenAI): Scaled up to 175 billion parameters, could perform many language tasks with minimal training

-

ChatGPT (2022, OpenAI): Made large language models accessible to the public, becoming the fastest-growing consumer application in history

Game-Playing AI

Deep learning combined with reinforcement learning (learning through trial and error) achieved remarkable game-playing abilities:

-

Atari Games (2013, DeepMind): A neural network learned to play dozens of Atari games, often surpassing human experts, using only raw pixel inputs and game scores instead of hand-coded game knowledge.

-

AlphaGo (2016, DeepMind): Defeated the world champion at Go, an ancient strategy game far more complex than chess. This was considered a decade ahead of expectations.

-

Dota 2 (2018, OpenAI): OpenAI's system defeated professional human teams at the complex multiplayer video game Dota 2.

-

StarCraft (2019, DeepMind): AlphaStar achieved professional-level play in StarCraft, a real-time strategy game requiring planning, adaptation, and complex decision-making.

These achievements demonstrated that neural networks could master extremely complex domains requiring strategy, intuition, and long-term planning.

Scientific Applications

Deep learning is accelerating scientific discovery:

AlphaFold (2020, DeepMind): Solved the "protein folding problem," predicting how proteins fold into 3D shapes from their amino acid sequences. This 50-year-old problem is crucial for understanding diseases and designing drugs. AlphaFold's solution was called one of the most important scientific breakthroughs of the decade.

-

Drug Discovery: Neural networks are accelerating the search for new medicines by predicting which molecules might work as drugs.

-

Climate Modeling: Machine learning is improving weather prediction and climate models.

-

Particle Physics: Neural networks help analyze data from particle accelerators like the Large Hadron Collider.

Self-Driving Cars

Companies like Tesla, Waymo (Google), Cruise (GM), and many others use deep learning extensively for autonomous vehicles:

-

Recognizing objects (pedestrians, vehicles, signs, road markings)

-

Predicting how other drivers will behave

-

Planning safe paths

-

Making split-second decisions

While fully autonomous cars aren't yet commonplace, the technology has progressed dramatically, and limited self-driving systems are deployed in specific areas.

The Rise of Generative AI

The most recent wave has been generative AI, systems that create new content:

-

DALL-E, Midjourney, Stable Diffusion: These systems generate images from text descriptions, creating realistic or artistic images on demand.

-

ChatGPT and Other Large Language Models: Can write essays, answer questions, write code, engage in dialogue, and perform many language tasks.

-

GitHub Copilot: Helps programmers by suggesting code.

-

Generative Video: Newer systems are beginning to generate realistic video.

This wave has made AI tangible to ordinary people. Suddenly, everyone can interact with powerful AI, not just tech enthusiasts.

By the early 2020s, the U.S. was home to the most advanced AI models in the world; GPT from OpenAI, Gemini from Google, and Claude from Anthropic. These systems were the direct descendants of the Perceptron. It was proof positive that American persistence, infrastructure, and investment could turn an academic curiosity into the foundation of a new economy.

The Ecosystem of Supremacy

America's dominance in machine learning wasn't just technical, for it was also institutional. The country's unique ecosystem of venture capital, elite research universities, and government funding created a self-reinforcing loop of innovation./p>

-

Universities like Stanford, MIT, Berkeley, and Carnegie Mellon trained the world's top machine learning researchers.

-

Venture capital from firms like Andreessen Horowitz and Sequoia fueled the explosive growth of AI startups.

-

Cloud infrastructure from Amazon, Microsoft, and Google provided the computational backbone for training massive models.

-

OOpen-source culture, exemplified by TensorFlow and PyTorch, spread American AI standards worldwide.

In essence, the U.S. exported technology as well as a philosophy of AI; open, entrepreneurial, and relentlessly scalable.

Challenges and Continuity

By the mid-2020s, the deep learning revolution began to reveal its limits. Training models required astronomical energy and data, sparking ethical and environmental concerns. China, Europe, and the Gulf states began challenging U.S. supremacy with their own AI ecosystems. Still, America's lead remained formidable, built over half a century of research, risk, and reinvention.

Machine learning and neural networks had become more than tools; they were symbols of American ingenuity. From Rosenblatt's Perceptron to OpenAI's GPT-5, the story of deep learning is a distinctly American one. It is a testament to the belief that even the most abstract ideas, if pursued long enough, can reshape the world.

Today, deep learning stands at a crossroads. The same nation that invented it now wrestles with its consequences; bias, automation, misinformation, and the shifting balance of global power. But history suggests that America will adapt once again. Just as it turned the logic machines of the 1950s into the generative models of the 2020s, it will likely turn today's ethical and technical dilemmas into the next wave of innovation.

The rise of machine learning and neural networks is not only a chapter in the history of technology, it is a continuation of the American experiment itself; to imagine, to build, and to teach machines to learn.

Links

Links

AI in America home page

Biographies of AI pioneers