Jeopardy!

Jeopardy!

Watson's Triumph

In February 2011, IBM's Watson supercomputer faced off against the two greatest human champions in Jeopardy! history—Ken Jennings, who had won 74 consecutive games, and Brad Rutter, the show's all-time money winner.

America's favorite quiz show, Jeopardy! is one of the most iconic and distinctive TV game shows ever created, built around a clever twist: contestants are given the answers, and they must respond with the correct questions.

🎯 Core Concept

Instead of asking questions and expecting answers, Jeopardy! flips the format.

Each clue is phrased as an answer, and contestants must reply in the form of a question, such as: “What is the Pacific Ocean” or “Who is Vera Rubin.” This reversal gives the show its signature rhythm and intellectual charm.

🧠 How the Game Works

The game is played by three contestants across three rounds:

1. Jeopardy Round

- A board of 6 categories, each with 5 clues of increasing difficulty.

Contestants choose a clue, hear the “answer,” and press a button to buzz in to respond.

2. Double Jeopardy

Same structure, but higher dollar values and two Daily Doubles - special clues where a contestant can wager any portion of their score, and possibly lose everything.

3. Final Jeopardy

- One last clue.

- Contestants secretly write their response and wager any amount of their earnings.

The final reveal often swings the entire game.

⚡ What Makes It Unique

- Fast-paced buzzing creates tension.

- Wide-ranging trivia—from Shakespeare to quantum physics to pop culture.

- The “question” format gives it an intellectual flair.

- Daily Doubles add strategy and risk.

Long-running champions (like Ken Jennings and Brad Rutter) create dramatic story lines.

🌟 Cultural Impact

Jeopardy! isn’t just a game show. It's pure Americana.

It’s a test of breadth and speed, a celebration of curiosity, a ritual for millions of viewers, and a proving ground for some of the smartest contestants in TV history. It’s one of the rare shows where knowledge, nerve, and timing coincide.

The Challenge

The Challenge

Jeopardy! presented unique difficulties for artificial intelligence.

Unlike chess or previous AI challenges, the game required understanding natural language filled with puns, wordplay, and cultural references. Clues might involve rhymes, metaphors, or require knowledge spanning history, literature, pop culture, and obscure facts. The system had to process these questions in seconds, generate answers, assess its confidence level, and decide whether to buzz in—all without any internet connection.

The Technology

The Technology

Watson was built over four years by a team of IBM researchers led by David Ferrucci. The name honored IBM founder Thomas J. Watson, and the project cost IBM approximately $3 million to develop.

The hardware consisted of a room-sized system with 90 IBM Power 750 servers, creating a cluster with 2,880 processor cores and 16 terabytes of RAM. During gameplay, Watson ran on its own stored data—no internet access was permitted. The entire system consumed about 85,000 watts of power, roughly equivalent to 85 homes.

The software, called DeepQA (Deep Question Answering), represented IBM's breakthrough approach. Rather than relying on a single algorithm, Watson used hundreds of different algorithms working in parallel. When presented with a clue, the system would:

- Parse the question using natural language processing to understand what was being asked

- Generate hundreds of potential answers by searching its massive database of encyclopedias, dictionaries, news articles, and other sources

- Evaluate each candidate answer using different algorithms that looked at evidence from multiple angles

- Assign confidence scores to each possibility

Select the best answer and decide whether its confidence was high enough to buzz in

Watson's database included the full text of Wikipedia, encyclopedias, literature, news articles, and databases—about 200 million pages of content. The system could process this information at around 500 gigabytes per second.

One technical challenge was the buzzer timing. Watson had a mechanical finger that physically pressed the buzzer, and IBM had to develop precise algorithms to time the buzz optimally—too early and it would be locked out, too late and the humans would beat it.

![]()

Deep Dive into DeepQA

Deep Dive into DeepQA

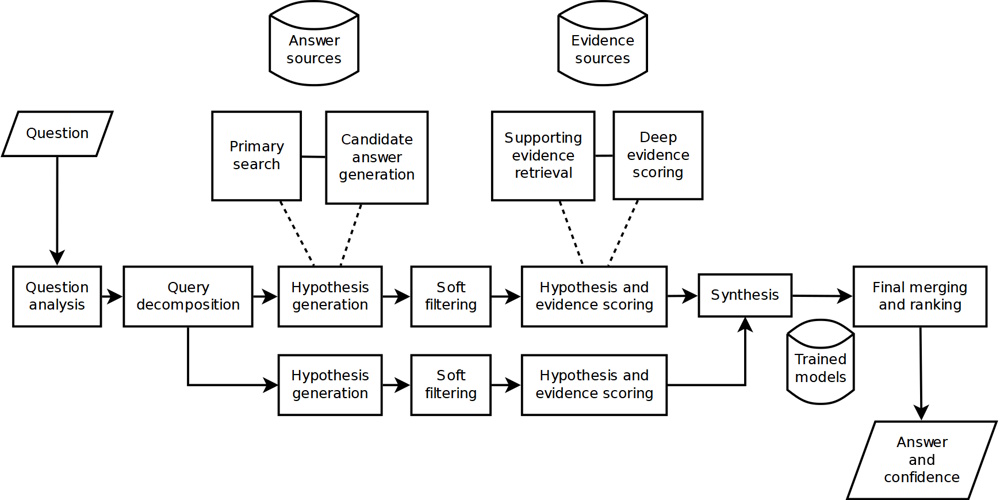

Watson's DeepQA system worked as a large, modular pipeline that generated many possible answers to a question, gathered evidence for each, and then used machine learning to pick the highest-confidence answer and decide whether to buzz in.

DeepQA was built as a "mixture of experts": many different NLP and IR components ran in parallel, each contributing features and confidence scores rather than a single final answer. No module had to be perfect; the system relied on combining many weak, noisy signals into a strong overall confidence estimate.

When Watson received a clue, it first analyzed the text to figure out what was being asked and how to search for it. This stage produced shallow parses, deep parses, logical forms, semantic role labels, named entities, relations, coreference links, and a predicted answer type (person, place, date, etc.).

Using the analyses, Watson launched several primary searches over a large, pre-built corpus of encyclopedias, reference works, and other texts. Each search returned documents and passages that were converted into 300-500 candidate answers per clue, favoring recall over precision so that the correct answer was likely somewhere in the candidate set.

For each candidate answer, Watson retrieved multiple supporting passages and other evidence, then ran many independent "scorers" on each question-answer-evidence combination. Scorers produced numeric or categorical features (e.g., lexical overlap, passage alignment, type matching, geographic consistency, temporal consistency) from unstructured text, semi-structured sources, and knowledge bases.

All the scores for a candidate were combined into a high-dimensional feature vector, and a learned, multi-stage classifier pipeline mapped these vectors to overall confidence scores and a ranking of answers. DeepQA used hierarchical machine learning to learn how to weight different scorers for different kinds of questions, turning thousands of raw feature values per clue into a single confidence number per answer.

On Jeopardy!, Watson then used its top answer and associated confidence, along with game state information (scores, clue value, position in the game), to decide whether to buzz. This same confidence machinery also informed Final Jeopardy and other strategic choices, tightly coupling the QA pipeline to game play.

The Match

The Match

The exhibition match, held over three episodes (February 14-16, 2011), ended with Watson decisively winning $77,147 to Jennings' $24,000 and Rutter's $21,600.

Watson's performance was both impressive and occasionally baffling. It dominated most categories, particularly those requiring pure factual recall.

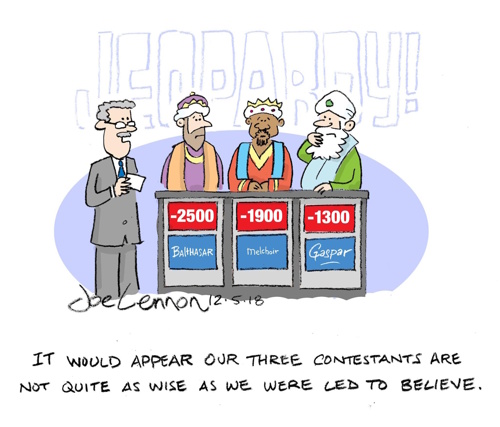

However, it made some memorable mistakes. In Final Jeopardy of the first game, Watson answered "What is Toronto?????" for a question about U.S. cities, despite Toronto being in Canada. The multiple question marks revealed the system's low confidence in its own answer.

The machine's voice, a synthetic tone that pronounced "Jeopardy!" as "JEH-per-dee," became iconic. Watson's avatar on the screen displayed different colors to indicate its confidence level and processing state.

Ken Jennings graciously acknowledged defeat, writing beneath his Final Jeopardy answer in the last game: "I for one welcome our new computer overlords"—a reference to the TV show The Simpsons.

The Aftermath

The Aftermath

Watson's victory demonstrated that AI could handle the ambiguity and complexity of human language in ways previously thought impossible.

This was fundamentally different from Deep Blue's chess victory in 1997, which relied on brute-force calculation. Watson had to understand context, culture, and nuance.

IBM quickly pivoted Watson from game show contestant to commercial applications. The technology was applied to healthcare, helping doctors diagnose diseases and recommend treatments by analyzing medical literature and patient records. Financial services, customer service, and business analytics followed. Watson became a brand for IBM's AI initiatives, now branded as watsonx.

However, the commercial success proved more challenging than the Jeopardy! victory. Watson's healthcare applications faced difficulties with real-world medical complexity, and some high-profile partnerships were scaled back or ended. The technology required significant customization for each industry, and early promises of revolutionary transformation took longer to materialize than anticipated.

Still, Watson's Jeopardy! moment remains a landmark in AI history. It showed that machines could process natural language at superhuman levels, accelerated research in question-answering systems, and captured public imagination about AI's potential in ways that influenced everything from Siri to modern large language models. The exhibition demonstrated that artificial intelligence could compete with humans in domains requiring knowledge, language understanding, and split-second decision-making.

The Showdown (humor)

The Showdown (humor)

Where a giant beige box basically flexed on two of the greatest human trivia nerds ever assembled

Picture this: February 2011. Jeopardy! producers are like, "What if we pit the two most unstoppable humans - Ken Jennings (74-game streak legend) and Brad Rutter (biggest money winner ever) - against a machine? Ratings gold!"

IBM rolls in with Watson: basically a room full of IBM Power 750 servers, 90+ processors, 16 terabytes of RAM, and a diet consisting entirely of ingested Wikipedia plus every book, dictionary, and Jeopardy! clue they could legally slurp. It didn't have ears or eyes, just text fed to it super fast. No buzzer hand; it had its own electronic finger on a hair-trigger solenoid. Humans had to physically stab a button. Advantage: robot.

Game 1 highlights (the funny parts):

Watson absolutely demolished the humans in buzzing speed. It was like watching two guys try to race a Tesla with Big Wheels tricycles. Ken and Brad would lean forward dramatically, but Watson was already done answering before their neurons finished firing.

Then came the now-legendary Final Jeopardy moment that still makes AI people cringe-laugh.

Category: U.S. CITIES

Clue: "Its largest airport is named for a World

War II hero; its second largest, for a World War II battle."

Correct response: What is Chicago? (O'Hare & Midway)

Ken writes: What is Chicago?

Brad writes: What is Chicago?

Watson

confidently writes: What is Toronto????

and then bets $947 (a hilariously small wager for a machine with effectively infinite money confidence).

Alex Trebek deadpans: "No."

Watson's avatar face just sits there,

unblinking.

The audience loses it. Ken later joked he almost felt bad for the computer... almost.

Why Toronto? Watson saw "largest airport" → "largest Canadian city" logic leak, got confused by weak category associations, and went full Canada mode. Humans would never make that leap. Machine did. Classic overthink.

Watson's blunder prompted an IBM engineer to wear a Toronto Blue Jays jacket to the recording of the second match.

Game 2: Watson came back even stronger, buzzing like it owed the humans money. At one point it answered a category about "rhyming answers" perfectly while Ken and Brad were still processing the clue. Ken later admitted he started feeling like he was playing against a god - a very fast, very smug god.

Post-game vibes:

Ken Jennings famously wrote on his Final Jeopardy screen (under his answer): "I for one welcome our new computer overlords" (A nod to The Simpsons' Kent Brockman line - pure gold.)

Brad Rutter, ever the chill pro, just smiled and said something like, "Well, that happened."

IBM gave Watson $1 million prize money, which it immediately "donated" to charity because computers don't need yachts.

Ken later said the experience was surreal: "It felt less like competing against a player and more like competing against Jeopardy! itself." If, that is, Jeopardy! had been huffing Red Bull and Wikipedia for four years. Ken also quipped, "Quiz Show Contestant may be the first job made redundant by Watson, but I'm sure it won't be the last."

The punchline everybody still quotes:

Watson didn't just beat the best humans at trivia. It beat them at trivia while occasionally thinking Toronto was an American city, and still won by a landslide.

Moral of the story? Never underestimate a machine that reads the entire internet for breakfast, but also definitely roast it when it thinks "US Cities" includes Canada.

And yes, Ken still has nightmares about buzzing sounds he can't physically make.

Links

Links

Game playing page.

IBM's other victory over a human opponent: Deep Blue defeats Kasparov in chess.

External links open in a new tab:

- plato.stanford.edu/entries/artificial-intelligence/watson.html

- aaai.org/ai-magazine/the-ai-behind-watson-the-technical-article/

- thekurzweillibrary.com/how-watson-works-a-conversation-with-eric-brown-ibm-research-manager

- cbmm.mit.edu/sites/default/files/documents/watson.pdf

- ibm.com/history/watson-jeopardy

- en.wikipedia.org/wiki/IBM_Watson

Amazon:

- Jeopardy! 2026 Day Calendar with Jeopardy! questions for each day of the year

- Final Jeopardy Man vs. Machine and the Quest to Know Everything book