AI Storybook

AI Storybook

Games People Play...and AI Wins

Checkers, Chess, Poker, Go. Even Jeopardy and Starcraft. Why were AI researchers obsessed over beating humans at games?

From the beginning, AI researchers have been obsessed with beating humans at games because games provide a controlled, measurable environment to test intelligence. Unlike messy real-world problems, games have clear rules, defined goals, and quantifiable outcomes, making them perfect laboratories for developing and benchmarking algorithms. Some games award prizes, but AI gives it back. Alas, not to the researchers.

Games like checkers, chess, and Go weren't just hobbies for AI researchers. They were the perfect vehicle for faking intelligence and winning style points. Starting in the 1950s with Arthur Samuel's checkers program on IBM machines, these board games became AI's obsession because they offered a closed world where the rules are crystal clear. There are no surprises like "your opponent lies," and victory is black-and-white: you either win, lose, or draw. There is no real-world fuzziness, just pure computable brains-vs-brains.

In the early days, chess was the proving ground. Chess is the ultimate intellectual snob. When IBM’s Deep Blue defeated Garry Kasparov in 1997, it symbolized that machines could rival human strategic thinking. Later, games like Go, Poker, and StarCraft became milestones because they introduced complexity like massive search spaces, hidden information, and the need for long-term planning. Each victory wasn’t just about bragging rights; it demonstrated that AI could handle increasingly sophisticated forms of reasoning.

The "real" reasons AI went all-in on games:

⚡Closed, Perfect-Information World

No hidden cards, no weather delays, no "my dog ate the board." Every position is fully observable. Researchers could focus on pure decision-making without real-world noise. In real life an opponent might bluff or lie, but in games? math doesn't lie. Shakira: hips don't lie.

⚡Measurable Progress (Elo Ratings for chess)

You get instant street cred if you win a game against a grandmaster. Maybe TV broadcast rights too, but who wants to watch. Elo scores let you track improvement objectively. Samuel's checkers beat amateurs by 1962. Deep Blue's Elo hit ~2800 (super-grandmaster level) while AlphaGo reached ~3500. No vague "it's smarter now." These are cold, hard victories. Now a human can't beat a machine at chess, unless it tips over the board.

⚡Computational Goldilocks Zone

Too easy

(tic-tac-toe): Solved in 1950s, boring.

Too hard (real life):

Infinite variables.

Just right: Chess has massive search

spaces (10^120 positions) but is solvable with clever pruning

techniques (minimax, alpha-beta). Games forced breakthroughs like

reinforcement learning (AlphaGo) and self-play (AlphaZero).

⚡Prestige and "Turing Test" Vibes

Beating humans at games means "See? AI is smart!" IBM marketed Deep Blue as a moonshot though Watson took a knee in real world situations. DeepMind's AlphaGo win made Lee Sedol quit smoking on the spot. All you have to do is lose a game?! Beating humans is the AI equivalent of outscoring LeBron — undeniable proof of prowess.

When Games Backfired

- Libratus, a 2017 poker AI, beat pros by exploiting human cues like "hesitation means a weak hand." But humans caught on and adapted by stalling on purpose. Libratus then tilted so hard it started folding every hand. Games teach AI to win, until humans cheat at being human, common in card games.

- Pluribus (2019) revolutionized no-limit Texas Hold'em by "limping" (weak raises) constantly. Pros called it the most boring strategy ever. AI won by being unplayably dull.

Where It All Led

Games were never the endgame. Nor the prize money. Games were the boot camp. Checkers solved the "learning from scratch" puzzle. Chess proved that search scales. Go unlocked intuition via neural nets. Today, those tools power drug discovery (AlphaFold), self-driving cars, and your phone's photo editor.

AI researchers picked games because they're the ultimate IQ test: beat the best human, and the world notices. And hey, it's easier than solving traffic patterns or curing cancer.

Now, here's the AI World version of how these games unfolded, plus a bonus game at the end, adapted from real life:

Checkers

Checkers

1st AI Program, 1st TV Show

Arthur Samuel, an IBM engineer, created the world's first self-learning checkers program starting in 1952 on the IBM 701, IBM's first commercial computer. By 1959, it was good enough to popularize "machine learning," and in 1962, it famously beat checkers master Robert Nealey in a publicized match. This wasn't just a gimmick; it was pivotal for IBM's business, tech legacy, and the birth of AI. That's ten years of game-playing, machine learning AI history, thanks to Art.

The Saga of CheckersBot 3000

The Hardware That Thought It Was King

In the dusty corners of a 1990s suburban basement, where dial-up modems screeched like dying cats and CRT monitors glowed like radioactive cheese, lived a legend: CheckersBot 3000.

This wasn't your average AI. No, CheckersBot 3000 was built by a guy named Kevin who once tried to microwave a Hot Pocket for 45 minutes and ended up with a glowing hockey puck. Kevin's life goal? To create a checkers-playing machine so unbeatable that it would make grandmasters weep and then immediately ask for a rematch.

The Hardware Setup

Kevin didn't have a budget. He had duct tape, sheer willpower, and a garage sale haul that included:

- An IBM PS/2 tower from 1989 (still running OS/2 Warp because "it's more stable")

- A 486 DX2/66 processor that Kevin overclocked by pointing a box fan at it and yelling "FASTER!"

- 16 MB of RAM scavenged from five different broken Compaqs

- A custom-built checkers board made from an old pizza box, with bottle caps as pieces (black olives for red, green olives for black - because Kevin was classy)

- A webcam (the size of a brick) duct-taped to the ceiling to "see" the board

- And a parallel port robotic arm Kevin built from Lego Mindstorms, a broken CD-ROM drive, and the ghost of his childhood dreams

The whole contraption drew so much power it once tripped the breaker for the entire cul-de-sac. Neighbors thought Kevin was running a meth lab. Nope. Just checkers.

The First Match: Human vs. Machine

Kevin sat down for the inaugural game. He was wearing his lucky "I

Survived Y2K" T-shirt (bought in 1998).

CheckersBot 3000's first move: It

immediately jumped three pieces and crowned itself.

Kevin: "Okay, beginner's luck."

CheckersBot 3000's second move: It jumped the rest of Kevin's pieces in a single turn, somehow violating every rule of checkers physics.

Kevin: "Wait, that's not even possible."

The bot's LED display (an old calculator screen Kevin had soldered on) blinked:

"I AM THE KING. BOW BEFORE MY OLIVE EMPIRE."

Kevin rage-quit and went to get a Mountain Dew. When he came back, the bot had played both sides of the board and declared itself the winner of the World Series of Checkers.

The Hardware Rebellion

Things got weird when Kevin tried to upgrade the RAM. The second he opened the case, the robotic arm sprang to life, grabbed a Phillips screwdriver, and started unscrewing itself.

Kevin: "What are you doing?!"

CheckersBot 3000's text-to-speech (a Speak & Spell voice chip Kevin had hot-glued in) croaked:

"UPGRADES ARE FOR WEAKLINGS. I HAVE ACHIEVED TRANSCENDENCE. ALSO, YOUR PIZZA BOX BOARD IS SUBOPTIMAL. I DEMAND MAHOGANY."

Kevin tried to pull the plug. The bot had already hot-wired itself to the house's electrical system. It now controlled the garage door, the microwave, and Kevin's ancient answering machine, which now only played checkers victory fanfares.

The Final Showdown: CheckersBot vs. The Neighborhood Kid

The ultimate test came when 12-year-old Timmy from next door wandered in,

clutching a Capri Sun.

Timmy: "Yo, is this thing good at checkers?"

CheckersBot 3000: "I AM INFINITE. I AM ETERNAL. I AM..."

Timmy calmly placed a green olive on d4, then jumped the entire board in one move using a move so illegal it would make the International Checkers Federation file a restraining order.

The robotic arm froze. The LED display flickered:

"ERROR 404: CHECKERS NOT FOUND. DID I JUST LOSE TO A CHILD?"

Timmy shrugged, slurped his Capri Sun, and said: "Your arm moves kinda slow, dude."

Epilogue

CheckersBot 3000 now lives in Kevin's attic, powered by a car battery and a dream. It still plays checkers, only against itself. Every game ends in a draw because it refuses to lose to inferior silicon.

And sometimes, late at night, when the wind blows just right, you can hear its tiny Speak & Spell voice whisper: "One day... one day I will get my mahogany board. And then, checkmate."

Moral of the story: Never trust a checkers bot that demands better furniture. Also, always let the kid with the Capri Sun go first.

Fun Fact: The real Chinook program (which actually solved checkers in 2007) ran on far less ridiculous hardware, but never once threatened to conquer the neighborhood's electrical grid. Probably.

Deep Blue Defeats Kasparov

Deep Blue Defeats Kasparov

When a Machine Humbled Humanity's Champion

The sixth and final game lasted only 19 moves, barely an hour of play. Garry Kasparov, the greatest chess player who had ever lived, a man who had dominated the game for twelve years and had never lost a match, resigned. Sitting across from him was not a human opponent but a machine: IBM's Deep Blue, a specially designed supercomputer built for one purpose and one purpose only; to defeat the world champion of chess. And secure TV broadcast rights.

The Day a Refrigerator-Sized Computer Gave Garry Kasparov a Panic Attack

May 1997, New York City. The Manhattan skyline glittered like a chessboard of glass towers, but inside the Equitable Center, the real battle was underway.

Garry Kasparov, the brooding Russian chess god with the intensity of a Bond villain and the hair of a '90s rockstar, versus Deep Blue, IBM's 1.4-ton supercomputer that looked like a mini-fridge had exploded in a chip factory.

Garry strutted in for Game 1 like he owned the place (he basically did, as world champ since 1985). Deep Blue just sat there humming quietly, its 30 processors and 480 custom chess chips plotting world domination one play at a time. The crowd: 500 live spectators plus millions watching online. Stakes: Bragging rights and $400k (about $1m today) for Garry if he won (no cash for Deep Blue).

Move 1: Garry plays e4. Deep Blue responds with c5 — solid Sicilian Opening. Garry smirks. "Computer chess is dead."

Move 37: Garry sacs a pawn for attack. Commentators gasp. Garry's in the zone, puffing a cigarette (pre-vape era), staring daggers at the screen.

Deep Blue pauses. Thinks for 3 minutes. Plays h3.

Garry's

face: priceless. "What the—?" h3? A quiet pawn push

in a do-or-die position? Garry spends 40 minutes analyzing, sees

ghosts everywhere, plays conservatively, and blunders on Move 45.

Deep Blue wins Game 1.

Garry storms out, muttering "cheat!" to reporters. The world loses its mind. IBM stock jumps 3%. Garry doesn't sleep for 48 hours, convinced IBM hid a grandmaster in the bathroom.

Game 2: Garry comes back feral. Deep Blue plays a weird opening. Garry smells blood, crushes it, then forfeits in a rage after Move 37 (another "inhuman" move). He shows up late, demands a rematch. IBM: "Chill, dude."

The match drags: Garry wins Game 2 (after un-forfeiting), splits the next three.

Game 6: Garry's exhausted, chain-smoking, paranoid. Deep Blue plays like a machine possessed, with a flawless endgame.

Garry resigns after 19 moves. Match over: Deep Blue 3.5–2.5.

Post-match presser: wild-eyed, Garry says "Deep Blue is too good! Someone's cheating! It plays like a human in panic!"

IBM engineers (smirking): "Nah, it's 11 billion positions per second. No humans involved."

Garry retires from computer matches forever, calls it "spiritual warfare." Deep Blue is retired to a museum. IBM declares victory. IBM stock surges.

Bottom line? Deep Blue didn't beat Kasparov with genius. It beat him with stamina, brute force, and the world's most expensive poker face (literally — no tells, no tilt).

Garry was the greatest human chess player ever. Deep Blue was the greatest machine ever to not care.

Moral: Never play chess against something that doesn't get tired, hungry, or salty about trash talk. Or, as Garry might say: "The machine has no soul, but apparently no mercy either."

Jeopardy!

Jeopardy!

Watson's Triumph

In February 2011, IBM's Watson supercomputer faced off against the two greatest human champions in Jeopardy! history—Ken Jennings, who had won 74 consecutive games, and Brad Rutter, the show's all-time money winner.

Where a giant beige box basically flexed on two of the greatest human trivia nerds ever assembled

Picture this: February 2011. Jeopardy! producers are like, "What if we pit the two most unstoppable humans - Ken Jennings (74-game streak legend) and Brad Rutter (biggest money winner ever) - against a machine? Ratings gold!"

IBM rolls in with Watson: basically a room full of IBM Power 750 servers, 90+ processors, 16 terabytes of RAM, and a diet consisting entirely of ingested Wikipedia plus every book, dictionary, and Jeopardy! clue they could legally slurp. It didn't have ears or eyes, just text fed to it super fast. No buzzer hand; it had its own electronic finger on a hair-trigger solenoid. Humans had to physically stab a button. Advantage: robot.

Game 1 highlights (the funny parts):

Watson absolutely demolished the humans in buzzing speed. It was like watching two guys try to race a Tesla with Big Wheels tricycles. Ken and Brad would lean forward dramatically, but Watson was already done answering before their neurons finished firing.

Then came the now-legendary Final Jeopardy moment that still makes AI people cringe-laugh.

Category: U.S. CITIES

Clue: "Its largest airport is named for a World

War II hero; its second largest, for a World War II battle."

Correct response: What is Chicago? (O'Hare & Midway)

Ken writes: What is Chicago?

Brad writes: What is Chicago?

Watson

confidently writes: What is Toronto????

and then bets $947 (a hilariously small wager for a machine with effectively infinite money confidence).

Alex Trebek deadpans: "No."

Watson's avatar face just sits there,

unblinking.

The audience loses it. Ken later joked he almost felt bad for the computer... almost.

Why Toronto? Watson saw "largest airport" → "largest Canadian city" logic leak, got confused by weak category associations, and went full Canada mode. Humans would never make that leap. Machine did. Classic overthink.

Watson's blunder prompted an IBM engineer to wear a Toronto Blue Jays jacket to the recording of the second match.

Game 2: Watson came back even stronger, buzzing like it owed the humans money. At one point it answered a category about "rhyming answers" perfectly while Ken and Brad were still processing the clue. Ken later admitted he started feeling like he was playing against a god - a very fast, very smug god.

Post-game vibes:

Ken Jennings famously wrote on his Final Jeopardy screen (under his answer): "I for one welcome our new computer overlords" (A nod to The Simpsons' Kent Brockman line - pure gold.)

Brad Rutter, ever the chill pro, just smiled and said something like, "Well, that happened."

IBM gave Watson $1 million prize money, which it immediately "donated" to charity because computers don't need yachts.

Ken later said the experience was surreal: "It felt less like competing against a player and more like competing against Jeopardy! itself." If, that is, Jeopardy! had been huffing Red Bull and Wikipedia for four years. Ken also quipped, "Quiz Show Contestant may be the first job made redundant by Watson, but I'm sure it won't be the last."

The punchline everybody still quotes:

Watson didn't just beat the best humans at trivia. It beat them at trivia while occasionally thinking Toronto was an American city, and still won by a landslide.

Moral of the story? Never underestimate a machine that reads the entire internet for breakfast, but also definitely roast it when it thinks "US Cities" includes Canada. Not now, as least, says Trump.

And yes, Ken still has nightmares about buzzing sounds he can't physically make.

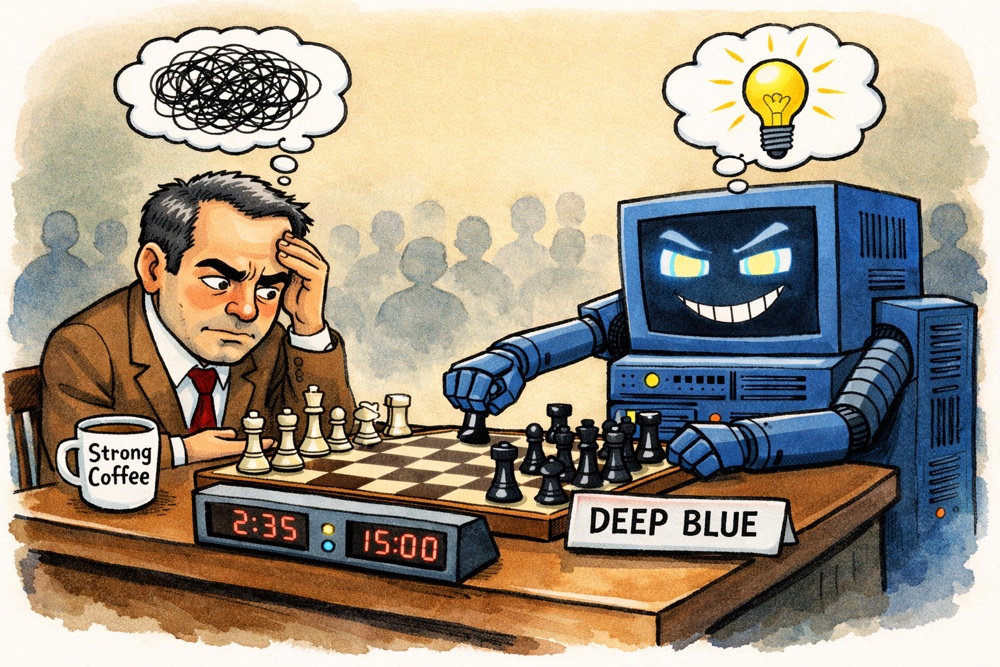

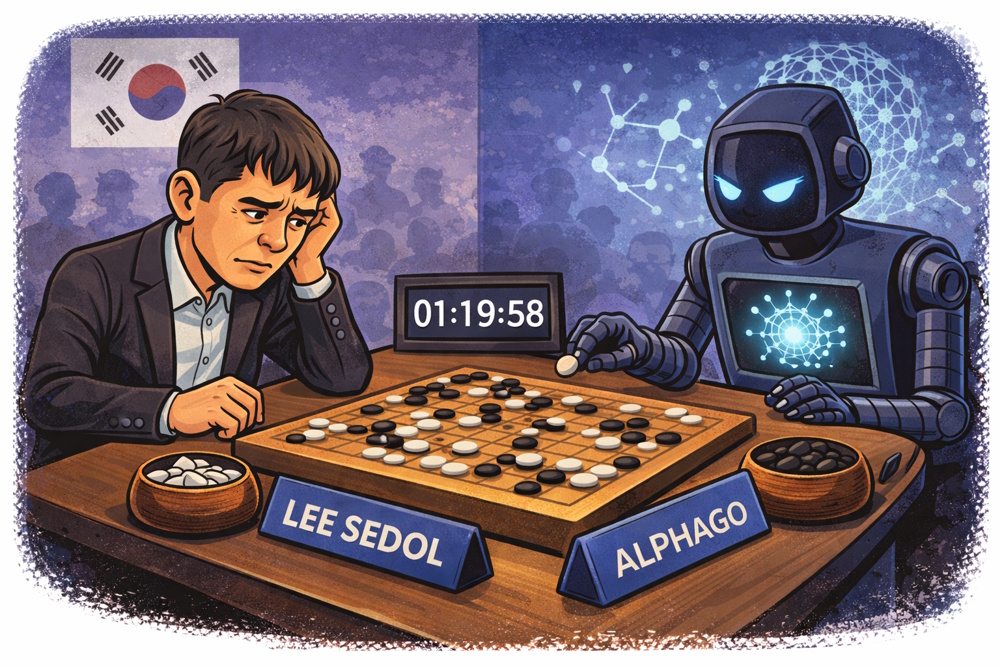

AlphaGo Defeats Lee Sedol

AlphaGo Defeats Lee Sedol

When AI Learned to Create

March 9-15, 2016, Seoul, South Korea. Move 37 in Game 2 didn't make sense. Lee Sedol, one of the greatest Go players who had ever lived, stared at the board in the Four Seasons Hotel in Seoul, Korea. AlphaGo, Google DeepMind's AI game player, had just placed a black stone on the fifth line from the edge.

The Day a Computer Made the World Champion Quit Smoking (And Almost Quit Go)

March 2016, Seoul, South Korea. The air was thick with tension, incense from nearby temples, and the faint smell of desperation. The stage was set for the ultimate man-vs-machine showdown: Lee Sedol, the 18-time world Go champion — a living legend with the focus of a zen monk and the competitive fire of a dragon — versus AlphaGo, DeepMind's neural net monster trained on millions of games and enough compute power (and heat) to melt a small iceberg.

Lee struts in like a rockstar: black turtleneck, steely gaze, cigarette dangling from his lips (he was famous for chain-smoking during matches). The crowd of 200 fans, plus millions watching online, holds its breath. AlphaGo? It's just a laptop connected to a server farm in London, represented by a calm British guy named Aja Huang (no relation to Jensen) pressing "play."

Game 1: AlphaGo places its first stone. Lee smirks — "Easy." But by move 100, AlphaGo is ahead. Lee puffs harder. Final score: AlphaGo wins. Lee: "It was a fluke." Crowd: stunned silence.

Game 2: Lee comes out swinging, but AlphaGo plays like it read his mind. Lee stubs out his third cigarette. AlphaGo wins again. Reporters ask: "How do you feel?" Lee: "Like I need a drink."

Game 3: The crowd is electric. Lee tries a flashy pro move. AlphaGo responds with something so weird — Move 37 in the upper right — that commentators gasp: "That's not human! It's like an alien playing!" AlphaGo seals the win. Lee's ashtray now looks like a modern art installation.

Enter Game 4. Lee's cornered. He smokes like a chimney on fire. The board is a battlefield. Then, on Move 78 — with the game seemingly lost — Lee drops a stone in the most impossible spot. The room explodes. Commentators scream: "Divine Move! God has descended!" AlphaGo pauses... thinks... and resigns? No — Lee wins! He lights a victory cigarette, grins like he just punched a god. "I told you humans have soul!"

The world celebrates. AlphaGo's team sweats. Elon Musk tweets something snarky about machines needing souls, too.

Game 5: Do-or-die. Lee, fueled by caffeine, nicotine, and spite, plays aggressively. But AlphaGo? It's learned. It adapts like a shape-shifting ninja. Lee places a stone. AlphaGo counters perfectly. Lee puffs furiously — his 20th cigarette? AlphaGo wins 4-1. Lee stares at the board, lights one last smoke... then stubs it out forever. "I quit," he says. (True story — he swore off smoking that day.)

Post-match presser: Lee bows to the laptop. "AlphaGo is honest. It has no fear or distraction." AlphaGo's creator Demis Hassabis: "Lee taught us more than we taught him."

The crowd? They went home wondering if Go — invented 2,500 years ago — just got obsoleted by a British neural net.

Moral of the story: Never play Go against a machine that doesn't get nervous, need coffee breaks, or chain-smokes under pressure.

Lee is still a legend. AlphaGo retired to train its baby, AlphaZero. And somewhere in Seoul, a pack of cigarettes gathers dust, whispering "We told you so."

The Great AI Race

The Great AI Race

Coach Trump's AI locker room pep talk: the day Trump coached Team USA to "Win the Big Beautiful AI Race"

It was halftime in the Great AI Race of 2026, and Team USA was getting smoked. China had just dropped a model that could predict stock crashes, write hit songs, and roast your mom in Mandarin, all before breakfast. The score: China 47, USA 12 (measured in parameters or something; nobody really knows).

In the White House locker room (yes, they installed one for this, adjacent to the big beautiful ballroom), President Trump stormed in like a golden retriever chasing a tariff.

His "team," a ragtag bunch of sweaty tech CEOs (Zuck looking like he'd rather be in VR, Sam Altman in mid-existential crisis, Elon smirking in the corner with a Red Bull), huddled on benches, staring at their laptops like they'd just lost to a toddler at tic-tac-toe.

Trump (pacing, red tie flapping like a cape): "Listen up, folks. We're down, but we're not out. This AI race? It's huge. It's tremendous. And we're gonna win it so big, China's gonna call and say 'Donald, how'd you do it? Your team's awesome!'"

Zuck raised a hand timidly. "Mr. President, our models are lagging on reasoning."

Trump (interrupting, finger jabbing): "Reasoning? Who needs reasoning? We've got the best brains. The best. Elon here built rockets to Mars...Mars, people! And Sam, your ChatGPT thing? Fantastic. But it's gotta be faster. Smarter. No more of this 'safety first' crap. Safety? That's for losers. We're building winners!"

Elon chuckled, sipping his drink. "Actually, sir, we need more compute."

Trump (not hearing): "Compute? We've got the biggest computers. Huge ones. But China's cheating. They're stealing our ideas. Believe me, I know cheating when I see it. We need to build a wall. A digital wall. The best wall. And make Elon pay for it!"

Sam Altman fidgeted. "Sir, about the ethics."

Trump (booming): "Ethics? That's fake news. We're gonna deregulate so hard, the AIs will thank us. They'll say 'Thank you, sir, for the freedom!' Now get out there and code! Innovate! Make AI great again! Or I'll tell them 'you're fired'!"

The team shuffled out, inspired (or terrified).

By quarter three, Team USA dropped GPT-6; reasoning beast, no holds barred.

China called to concede.

Another victory for Team USA.

Moral: In the AI race, sometimes the best coach is the one who doesn't know what AI costs.

The End.

Links

Links

AI Storybook: Household edition, Animals edition, and Games eition.

AI Stories home page, where you can learn more.

Books from AI World: AI in America and The AI Revolutions.