AlphaGo Defeats Lee Sedol

AlphaGo Defeats Lee Sedol

When AI Learned to Create

March 9-15, 2016, Seoul, South Korea

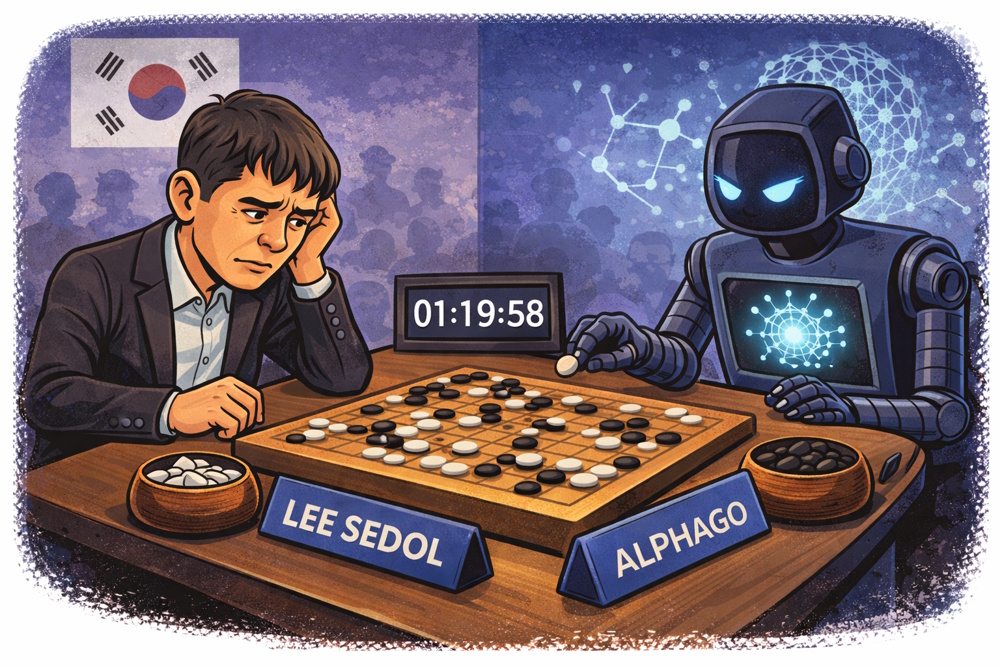

Move 37 in Game 2 didn't make sense. Lee Sedol, one of the greatest Go players who had ever lived, stared at the board in the Four Seasons Hotel in Seoul, Korea. AlphaGo, Google DeepMind's AI game player, had just placed a black stone on the fifth line from the edge.

This wasn't how Go was played. Thousands of years of accumulated wisdom said you don't play on the fifth line in that situation. It violated intuition. It looked like a mistake, the kind of move a beginner might make.

The commentators were confused. The professional Go players watching were puzzled. Lee Sedol himself sat in silence for nearly fifteen minutes, trying to understand what he was observing.

But it wasn't a mistake. It was beautiful. Move 37 would later be called one of the most creative moves in Go history. It was a move so far beyond conventional thinking that no human would have conceived it.

And it came from a machine.

By the end of the five-game match, AlphaGo had won 4-1, defeating one of humanity's strongest players at the most complex game ever devised.

The victory meant something different than Deep Blue's chess triumph nineteen years earlier. This wasn't brute force defeating human intuition, like Deep Blue's victory over Garry Kasparov. This was something that looked like creativity, intuition, and artistry emerging from silicon and mathematics. This was AI that didn't just calculate. It seemed to understand. It didn't just win. It played... beautifully.

The Go community didn't react with devastation like Kasparov after Deep Blue. Instead, they were awed and inspired. One professional player cried tears of joy watching AlphaGo's moves, calling them beautiful beyond anything he had seen.

This is the story of how that happened. It is the story of the people, the technology, the match, and what it meant for humanity's relationship with artificial intelligence.

The Game of Go

The Game of Go

Why It Matters

The game of Go is older than chess. Invented in China over 2,500 years ago, it's played on a 19×19 grid with black and white stones. The rules are simple:

Players alternate placing stones on intersections

Stones surrounded by the opponent are captured

The goal is to control more territory than your opponent

That's it. Four rules. A child can learn them in minutes. But the simplicity is deceptive. Go is staggeringly complex:

Complexity Comparison:

Chess: ~10^120 possible games, ~35 legal moves per position on average

Go: ~10^250 possible games (more than atoms in the universe), ~250 legal moves per position

After just a few moves in Go, the number of possible game states exceeds anything in chess. The game tree is so vast that brute-force calculation—the approach that worked for Deep Blue—is utterly hopeless.

Why Computers Couldn't Play Go

For decades, Go was considered AI's holy grail. It was regarded as the one game computers might never master.

Computers have been playing games for almost as long as computers have existed, and from the very beginning, researchers treated games as a proving ground for machine intelligence. Early computers of the 1940s and 1950s were massive, expensive machines, yet programmers still found ways to make them play simple games. They didn't play them as fun distractions, but as controlled environments to test logic, strategy, and human-machine interaction. These early experiments helped the public understand what computers could do at a time when most people saw them as mysterious mathematical devices called "electronic brains."

By the early 1960s, games became a cultural and technical catalyst. Created at MIT in 1961, Spacewar was one of the first true computer video games, running on a DEC PDP-1 minicomputer. It demonstrated real-time graphics, interactive control, and the idea that computers could simulate dynamic worlds. This marked the beginning of a long relationship between computing and games, with each pushing the other forward.

As computers grew more powerful, the ambition shifted from simply playing games to mastering them. Games like checkers, chess, and Go became benchmarks for artificial intelligence because they required planning, strategy, and foresight. Each breakthrough, whether in search algorithms, heuristics, or machine learning, was measured by whether a computer could outperform a human expert. This desire to "beat the game" wasn't about competition alone; it was a way to measure progress in reasoning, pattern recognition, and decision-making. Over time, this drive helped transform games from curiosities into laboratories for AI research, influencing everything from modern machine learning to robotics and autonomous systems.

Chess had been conquered because:

Positions are easy to evaluate (count material, assess piece placement)

The game tree is searchable with powerful computers

Tactics and calculation matter most

Go resisted computers because:

Positions are nearly impossible to evaluate numerically

The game tree is too vast to search effectively

Strategy and intuition matter more than calculation

"Good" and "bad" positions are subtle and contextual

In chess, being up a queen usually means you're going to win. It’s easy to quantify. In Go, who's ahead is often unclear even to experts until late in the game. Evaluating Go positions requires deep understanding, pattern recognition, and intuition. These are quintessentially human skills.

The State of Computer Go (1990s-2015)

While chess computers reached grandmaster strength in the 1990s and superhuman play by 2005, Go computers remained embarrassingly weak:

1990s: Computer Go played at strong amateur level (5-10 kyu)

2006: Best programs played at low dan level (just above amateur status)

2015: Top programs reached 6-7 dan (strong amateur/weak professional)

Professional Go players stand at 9 dan. Lee Sedol was 9 dan professional, representing the top 0.01% of players worldwide.

The gap between the best computers and the best humans remained enormous. Professionals could give computer programs 4-5 stones handicap and still win easily.

AI researchers believed conquering Go would require different approaches than chess, not brute force like Deep Blue, but something resembling human intuition and pattern recognition. Some predicted it would take until 2025 or beyond, if at all.

They were wrong.

The People

The People

DeepMind's Visionaries

Demis Hassabis - The Dreamer

Demis Hassabis is one of the most influential figures in modern artificial intelligence, known for blending deep scientific curiosity with entrepreneurial drive. Born on 27 July 1976 in London to a Greek Cypriot father and a Chinese Singaporean mother, he showed early signs of unusual talent. By age four he was playing chess, and by thirteen he had already become a master-level competitor. His early brilliance wasn’t limited to the board: at seventeen he helped code the hit video game Theme Park, a project that foreshadowed his lifelong fascination with intelligence, both human and artificial.

After earning a Double First in Computer Science from the University of Cambridge, Hassabis moved through the gaming industry, contributing to Bullfrog Productions and later founding Elixir Studios. Driven by a desire to understand the mechanics of memory and cognition, he pursued a PhD in cognitive neuroscience at University College London.

His PhD research studied memory and imagination in the hippocampus. He discovered that the same brain systems used for remembering the past also construct imagined futures. This insight—that intelligence involves simulating and learning from imagined scenarios—would influence AlphaGo's design.

In 2010, Hassabis co‑founded DeepMind, a company that would change the course of AI. Under his leadership, DeepMind produced a series of landmark achievements, most famously AlphaGo and AlphaFold (which solved the decades‑old challenge of predicting protein structures). These breakthroughs placed DeepMind at the center of global scientific innovation and earned Hassabis some of the world’s highest honors, including the Albert Lasker Award, the Breakthrough Prize in Life Sciences, the Canada Gairdner International Award, and the 2024 Nobel Prize in Chemistry.

Today, Hassabis serves as CEO of Google DeepMind and founder of Isomorphic Labs, where he continues to push the boundaries of AI in both scientific discovery and real‑world applications. His career reflects a rare fusion of creativity, scientific rigor, and strategic vision, qualities that have made him one of the defining architects of the AI era.

DeepMind - Founded on a Vision

In 2010, Hassabis co-founded DeepMind Technologies in London with Shane Legg (machine learning expert) and Mustafa Suleyman (entrepreneur).

Their mission statement was ambitious: "Solve intelligence, and then use that to solve everything else." Not "build AI for specific applications," but solve intelligence itself—create artificial general intelligence that could learn and reason like humans do.

Go was the perfect test case. If you could build AI that mastered Go using general learning principles (not hand-coded rules), you would have something approaching general intelligence.

Google Acquires DeepMind

In 2014 Google bought DeepMind for approximately $500 million. It was an enormous sum for a startup that had yet to release any products. It was a price Google was willing to pay, for Google saw what Hassabis was building: not just better search algorithms or ad targeting, but a path toward Artificial General Intelligence (AGI).

The acquisition gave DeepMind enormous resources: Google's computing power, data, expertise, money, and intellectual freedom. Google agreed DeepMind would remain independent, pursuing fundamental research rather than short-term commercial products.

David Silver - The Go Player

David Silver joined DeepMind as a research scientist. Unlike most AI researchers, Silver was passionate about Go. He was a strong amateur player, having reached 6 dan. He obtained a PhD from the University of Alberta studying reinforcement learning in Go. He had spent years thinking about how AI could learn to play Go.

Silver became the lead researcher on the AlphaGo project. His deep understanding of both Go and reinforcement learning would be essential to the challenge.

The AlphaGo Team

The core team included:

David Silver: Lead researcher, reinforcement learning expert

Aja Huang: 6-dan amateur Go player, engineer

Chris Maddison: Researcher specializing in Monte Carlo Tree Search

Dozens of engineers, researchers, and support staff

They had access to:

Google's vast computing infrastructure

Thousands of GPUs for training neural networks

Unlimited cloud computing resources

World-class expertise in machine learning

This wasn't a small team in Toronto working on gaming GPUs. This was a massive, well-funded effort by some of the smartest people in AI, backed by one of the world's most powerful technology companies. Advantage DeepMind.

The Technology

The Technology

How AlphaGo Works

AlphaGo was revolutionary because it combined multiple AI approaches in a novel way. Understanding it requires explaining several key concepts:

Neural Networks for Pattern Recognition

The Problem: How do you evaluate a Go position? With millions of possible board states, you can't have pre-programmed rules for each.

AlphaGo's Solution: Train neural networks to recognize patterns.

AlphaGo used deep convolutional neural networks (CNNs), the same architecture that powered AlexNet's ImageNet victory. These networks learned policy and value:

Policy Network: Predict what moves expert humans would play

Value Network: Evaluate how likely a position will lead to victory

Training the Policy Network

DeepMind gathered 30 million positions from 160,000 games played by strong human players (6-9 dan). They trained a neural network:

Input: Board position (19×19 grid)

Output: Probability distribution over all legal moves

Learning: Adjust to predict what move the human player actually made

After training, the policy network could approximate human intuition by examining a position and predict which moves a strong human would consider making.

Accuracy: The policy network predicted the expert's move 57% of the time. It was not perfect, but it was remarkably good for a machine. AlphaGo had learned to think like a human Go player.

Training the Value Network

Evaluating positions (who's winning?) is harder than predicting moves. DeepMind trained a separate network:

Input: Board position

Output: Probability that whoever controls the position will win

They couldn't just use human game data since the network would memorize specific positions rather than learning general evaluation. Instead, they had AlphaGo play millions of games against itself and learn from the outcomes. This self-play generated 30 million new positions, each with a known outcome.

The value network learned to evaluate positions based on which side ultimately won.

Monte Carlo Tree Search

Neural networks alone weren't enough. AlphaGo needed to search ahead to explore possible future moves and consequences.

But with 250+ legal moves per position, searching deeply is impossible. AlphaGo used Monte Carlo Tree Search (MCTS), a technique that:

Selects promising branches of the game tree to explore

Expands those branches by considering possible moves

Simulates games to completion using the policy network

Backpropagates results to update the tree

Instead of exhaustively searching all possibilities, MCTS focuses on the most promising variations, guided by the neural networks.

The Integration: Four Components Working Together

AlphaGo combined:

Fast Policy Network: Quick, simpler network for rapid move evaluation during search (2 microseconds per evaluation)

Slow Policy Network: More accurate network for selecting which moves to search (3 milliseconds per evaluation)

Value Network: Evaluates positions without simulating to the end

Monte Carlo Tree Search: Searches the game tree, guided by the networks

During a move:

MCTS builds a tree of possible move sequences

The fast policy network quickly evaluates many possible moves

The slow policy network identifies the most promising moves to search deeply

The value network evaluates positions without playing them out

The system combines all this information to choose the best move

The result was that AlphaGo could search far fewer positions than Deep Blue (thousands vs. millions), but each search was guided by deep pattern recognition that approximated human intuition.

Reinforcement Learning - Learning from Self-Play

After the networks were trained on human data and the system was integrated, AlphaGo played itself millions of times.

Each self-play game:

Started from random positions

Both "sides" were AlphaGo, trying to win

Outcomes were used to improve the policy and value networks

The system learned strategies humans had never discovered

This reinforcement learning allowed AlphaGo to go well beyond human knowledge by uncovering new strategies impossible for humans to discover.

Why This Approach Was Different From Deep Blue

While Deep Blue out-calculated humans, AlphaGo out-intuited them:

Deep Blue (Chess) |

AlphaGo (Go) |

|---|---|

Brute force search |

Selective, intuitive search |

Hand-coded evaluation |

Learned evaluation from data |

200 million positions/second |

~100,000 positions/second |

Custom hardware chips |

General GPUs + Google TPUs |

Chess-specific |

General learning principles |

No learning |

Continuous learning from self-play |

Tactical calculation |

Strategic understanding |

The Hardware

The Hardware

Distributed Computing Power

Unlike Deep Blue's custom chess chips, AlphaGo ran on:

For the Fan Hui Match (October 2015):

Distributed across many machines

Hundreds of CPUs

Dozens of GPUs for running neural networks

For the Lee Sedol Match (March 2016):

1,920 CPUs

280 GPUs

Distributed across many servers in data centers

Plus: Google TPUs

Google had developed Tensor Processing Units (TPUs). These are custom chips optimized for neural network calculations, particularly for matrix multiplications. AlphaGo was one of the first applications to use TPUs at scale.

While Deep Blue was a single specialized machine, AlphaGo was a distributed system running across Google's cloud infrastructure. It is massively parallel, with neural networks running on GPUs/TPUs and tree search distributed across CPUs.

Computing Cost: Estimated at thousands of dollars per game in cloud computing costs.

The Physical Setup

At the match venue, AlphaGo wasn't physically present. The computer:

Ran on Google servers (location undisclosed, likely multiple data centers)

Communicated via internet to a laptop at the match

An operator (Aja Huang) placed stones on the board for AlphaGo

Lee Sedol sat across from an empty chair

This setup was eerie. It depicted Lee fighting an invisible, distributed intelligence existing only in Google's cloud. And in Lee's head.

The Road to Seoul

The Road to Seoul

The Secret Match

Before challenging Lee Sedol, DeepMind tested AlphaGo against Fan Hui, the European Go Champion (2-dan professional; good, but not world-class).

The match was played in secret in London, October 2015. Result: AlphaGo won 5-0.

This was a shocking result. No computer had ever defeated a professional Go player in an even game. DeepMind published the results in the journal Nature in January 2016, announcing they were ready to challenge a top player.

Choosing the Opponent: Lee Sedol

Lee Sedol was one of the strongest Go players in history.

Born March 2, 1983, in South Korea's Sinan County, Lee Sedol emerged as one of the most formidable and imaginative Go players of the modern era. Turning professional at just 12 years old, he rose with unusual speed through the dan ranks, reaching 9-dan by age 21, the youngest ever to do so at the time. His style was famously aggressive, intuitive, and unorthodox, earning him the nickname "The Strong Stone" for his ability to seize back positions that seemed hopeless to others. Over the course of his career, he amassed 18 international titles, placing him second in history only to Lee Chang-ho. Sedol earned more than 50 domestic championships, achievements that cemented his place among the game's all-time greats.

Sedol's competitive peak in the 2000s and early 2010s was marked by streaks of dominance, including long runs of consecutive wins and a reputation for brilliance in high-pressure matches. His creativity at the board made him a fan favorite and a feared opponent; he was known for moves that defied conventional wisdom yet revealed deep strategic insight. By 2012, he became only the second player in history to surpass 1,000 career victories, a milestone that reflected both his longevity and excellence.

He wasn't the reigning world champion at the time of the match (Go has multiple championship systems), but he was top-5 in the world and considered one of the best.

Why Lee Sedol?

Strong enough to be a legitimate challenge

Agreed to play (some top players refused, not wanting to risk losing to a computer)

Charismatic and well-known

Spoke some English (easier for international audience)

The stakes:

$1 million prize fund ($1M if Lee won all 5 games, $150k for each game won, $150k to Lee even if he lost all games)

Match would be broadcast worldwide

Held in Seoul, South Korea—Go's spiritual homeland

The Build-Up

DeepMind heavily promoted the match:

Documentary film crew followed the event

YouTube livestream with commentary

International media attention

Framed as humanity's last stand in the game of Go

Fan reaction was mixed:

Many Go professionals were skeptical—the gap between 2-dan (Fan Hui) and 9-dan (Lee Sedol) is enormous

Some thought Lee would win easily, perhaps 5-0

Others worried that if AlphaGo could beat Fan 5-0, maybe it was stronger than anyone realized

Lee Sedol was confident but respectful. In press conferences. "I've heard it's quite strong, but I believe human intuition is still too advanced for computers," he said.

He predicted he would win 5-0 or 4-1.

The Match

The Match

Five Games That Changed Everything

Game 1 - March 9, 2016: The Awakening

AlphaGo had Black to start (a slight disadvantage). The opening proceeded normally, with both sides playing standard joseki (corner patterns).

AlphaGo's moves had a strange character. They weren't wrong, but they felt different; too slow here, too aggressive there, compared to normal, human play. At times Lee looked confused though he played well.

The middle game became complex. AlphaGo made several moves professionals thought were questionable. Commentators suggested Lee was ahead.

Then AlphaGo's strategy became clear. Its seemingly slow moves earlier had built a massive framework—a huge territorial structure. Lee's groups were alive but small. AlphaGo's groups controlled vast spaces.

Lee fought brilliantly, invading, reducing, creating complications. But AlphaGo defended accurately, calculating precisely, never making serious mistakes.

At move 186, Lee resigned. AlphaGo had won the first game.

Result: AlphaGo 1, Lee Sedol 0

The crowd was shocked. The Go world hadn't expected this outcome. Lee had played well—not perfectly, but strongly. AlphaGo had played better. And it didn't play like a computer. It played like a professional Go player. A strong one.

Lee: "I was very surprised. I didn't expect AlphaGo to play such a perfect game."

Game 2 - March 10, 2016: Move 37 Drama

This game would become legendary. Lee had Black. The game proceeded normally through the opening. Both sides built frameworks, and fought for influence.

Then came Move 37.

AlphaGo (playing White) placed a stone on the fifth line—a shoulder hit that violated conventional wisdom.

Immediate reaction:

Commentator Michael Redmond (9-dan professional): "I thought it was a mistake." The YouTube livestream chat exploded with confusion. Professional players watching around the world were baffled.

Lee Sedol stared at the board. He stood up, left the room, returned, sat down, stared more. He spent nearly 15 minutes thinking—an eternity in Go.

Why it seemed wrong:

Standard Go wisdom says you don't play on the fifth line in that situation. It's too loose, and doesn't put enough pressure, leaving weaknesses. Thousands of years of accumulated knowledge said this move was suboptimal.

Why it was brilliant:

Move 37 was subtle and strategic, looking 50+ moves ahead. It created aji (latent potential) that AlphaGo would exploit later. It was a move a human might make if they could read 50 moves deep—but humans can't.

It was a move no human would have found. It was creative; not what we expect from a machine.

The aftermath:

Lee never recovered. The psychological impact was enormous. If AlphaGo could see things he couldn't, how could he trust his own analysis?

The game continued. AlphaGo played brilliantly, while Lee struggled. At move 211, Lee resigned.

Result: AlphaGo 2, Lee Sedol 0

The Go community was in shock. Move 37 was being called one of the most creative Go moves ever played. And it came from a machine.

Some professionals were crying—tears of joy, not sadness. They'd witnessed something beautiful.

Fan Hui (the European champion who had lost to AlphaGo 5-0) said, "It's not a human move. I've never seen a human play this move. So beautiful. So beautiful."

Lee Sedol: "Yesterday I was surprised. But today I am speechless."

Game 3 - March 12, 2016: Perfection

After two losses, Lee desperately needed a win. He'd lost to the greatest Go players—Ke Jie, Park Junghwan—but always competed. This was different. He felt outmatched.

Game 3 started well for Lee. He built a large territorial framework. At move 48, commentators thought Lee might be slightly ahead. Then AlphaGo launched a brilliant invasion and reduction campaign. Over the next 100 moves, it systematically eroded Lee's territory while building its own. The play was surgical; precise, relentless, nearly perfect. Every move served a purpose. No wasted stones. No weaknesses created.

Lee fought hard, finding the best human moves he could. But AlphaGo's responses were always just slightly better. It was like watching a grandmaster play a strong amateur—the amateur plays well but is always just behind.

At move 176, Lee resigned.

Result: AlphaGo 3, Lee Sedol 0

The match was over. AlphaGo had won. Game 4 and 5 would be played for pride and the remaining prize money, but the outcome was decided.

The Go world was in a state of wonder tinged with melancholy. They had witnessed Go played at a level beyond human ability. It was beautiful, awesome, and somehow bittersweet.

Lee at the press conference was visibly emotional: "I'm very sorry that the match is over already. I wanted to show a better result, a better score. The loss is mine alone. AlphaGo played a nearly perfect game."

Game 4 - March 13, 2016: Lee Strikes Back

Lee had one goal: win a single game to prove humans could still compete.

AlphaGo had Black. The opening was aggressive. Both sides fought for every point.

Then something magical happened.

At move 78, Lee played a wedge move—brilliantly creative, aggressive, and unexpected. It was Lee's Move 78, his answer to AlphaGo's Move 37.

AlphaGo faltered.

The commentators noticed immediately—AlphaGo's moves became slower (using more time), less certain. It was struggling.

Lee had found a blind spot—a situation AlphaGo hadn't learned to handle. Its policy network and value network were giving conflicting signals. The MCTS was exploring increasingly desperate variations.

AlphaGo made several weak moves—not blunders exactly, but sub-optimal responses that compounded. Its position deteriorated.

Lee pressed the advantage brilliantly, playing some of the best Go of his career. He was ahead, and he knew it.

At move 180, AlphaGo resigned.

Result: AlphaGo 3, Lee Sedol 1

The room erupted in applause. Lee had won. Humans had won. Not the match, but a game. Proof that human creativity could still find what machines missed.

Lee: "This is just a single game. I've already lost the match. But this one game is so valuable. It means humans haven't completely lost to AI yet."

The DeepMind team was thrilled—not disappointed. They'd learned something. AlphaGo had weaknesses. They could improve it.

Demis Hassabis: "Losing this game will make AlphaGo stronger in the future."

Game 5 - March 15, 2016: The Finale

The final game. Lee had White (slight advantage). He played aggressively, trying to create the complexity where he'd succeeded in Game 4.

But AlphaGo had adjusted. It played more carefully, avoiding the kinds of positions where Lee had found success.

The game was close—the closest of the match. For much of the game, it was unclear who was ahead. Lee fought brilliantly. AlphaGo defended accurately.

In the end, AlphaGo's precision in the endgame—counting and efficiency in the final stages—gave it a small but decisive advantage.

Lee resigned at move 281.

Final Result: AlphaGo 4, Lee Sedol 1

The match was over.

The Aftermath

The Aftermath

Immediate Reactions

Lee Sedol's Response: At the final press conference, Lee was gracious and philosophical:

"AlphaGo is stronger than I thought. I didn't know that AlphaGo would play such a perfect Go. I'll have to reconsider the game of Go. Previously, I thought Go was so beautiful and flawless, and AlphaGo made me realize it's not. I feel like Go was made for AlphaGo. Perhaps I was the better player in the past, but now, AlphaGo is better."

He was emotional, humble, and honest. There was no Kasparov-like anger or claims of cheating. Just acknowledgment that he'd been beaten by something remarkable.

The Go Community:

Unlike the chess world's devastation after Deep Blue, Go professionals reacted with wonder:

Many called it the most beautiful Go they'd ever seen

Professionals began studying AlphaGo's games, learning new strategies

Young players started mimicking AlphaGo's style

The level of Go play globally improved as people incorporated AlphaGo's insights

Fan Hui: "The program has changed my view of Go. I've played for years, but AlphaGo made me realize I was wrong about some fundamental things."

The AI Community:

Researchers were stunned. AlphaGo had exceeded expectations:

The timeline had been accelerated by 10 years

General learning approaches had conquered a domain thought to require hand-coded expertise

The combination of deep learning and search had proven extraordinarily powerful

DeepMind had proven something profound: you could use general machine learning principles to master domains requiring intuition and creativity, not just calculation.

The Technology Advances: AlphaGo Zero and Beyond

DeepMind didn't stop. After the Lee Sedol match, they asked: "What if we removed the human knowledge entirely?" So they created AlphaGo Zero.

AlphaGo Zero (October 2017):

Trained purely through self-play—no human game data

Started knowing only the rules, nothing about strategy

Played itself millions of times

After 3 days, it surpassed the version that beat Lee Sedol

After 40 days, it was vastly stronger than any previous AlphaGo

AlphaGo Zero's key innovation was it learned from scratch, discovering strategies humans had never found. Some of its moves resembled ancient Go wisdom that had been forgotten or dismissed. It was independently discovering thousands of years of accumulated knowledge plus inventing new strategies.

AlphaZero (December 2017):

Generalized the approach beyond Go

Same algorithm learned to play Chess, Shogi (Japanese chess), and Go

Trained from scratch in each game

Achieved superhuman play in Chess after 4 hours

Defeated Stockfish (world's strongest chess engine) decisively

This was the breakthrough: one algorithm, learning from first principles, mastering multiple games. This was closer to general intelligence than anything before it. Next, DeepMind created MuZero.

MuZero (2019):

Learned to play games without even being told the rules

Discovered the rules through playing

Mastered Atari games, Chess, Go, and more without game-specific code

Impact on Go

Rating Inflation:

After AlphaGo, human Go play improved globally:

Professionals studied AlphaGo's games like ancient texts

Strategies once considered unorthodox became standard

The average strength of professional play increased measurably

New Openings and Joseki:

AlphaGo invented or popularized moves that became standard:

Certain shoulder hits previously rare became common

Influence-based frameworks were reevaluated

The balance between territory and influence shifted

Some professionals said it was like a 2,000-year-old game had been revolutionized overnight.

AI Training Partners:

Professional Go players now train with AI:

AI programs analyze games, pointing out mistakes

Players test strategies against superhuman opponents

Young players improve faster than ever before

Paradoxically, AI made human Go better.

Lee Sedol's Later Career

After the match, Lee continued playing professionally, but the loss had affected him deeply.

He continued competing, but never recaptured his peak form. The psychological impact of the match seemed to linger. In 2019, Lee Sedol retired from professional Go at the age of 36 (relatively young).

His retirement statement:

"With the debut of AI in Go games, I've realized that I'm not at the top even if I become the number one through frantic efforts. Even if I become the number one, there is an entity that cannot be defeated."

It was poignant—the match had been three years earlier, but its shadow remained. He occasionally plays exhibition matches and does Go commentary, but his competitive career ended, in part at least because of AlphaGo.

After retiring from professional play, Sedol shifted his attention to teaching, research, and public speaking. He joined the Department of Artificial Intelligence at UNIST, where he explored how Go's principles - pattern recognition, long-term planning, and positional judgment - could inform new approaches to AI. Today, he remains a revered figure not only in Go, but also in the broader context of human creativity facing technological change.

DeepMind's Evolution

The AlphaGo victory established DeepMind's reputation as the world's premier AI research lab. They've since developed the following:

AlphaFold (2020): Solved the protein folding problem—predicting 3D protein structures from amino acid sequences. Called one of the most important scientific breakthroughs of the century.

Broader AI Research: Continuing work on artificial general intelligence, applying similar techniques to diverse domains.

Ethical AI: Demis Hassabis has become a voice for responsible AI development, warning about risks while advocating for beneficial AI.

The company remains semi-independent within Google (now Alphabet), pursuing fundamental research with commercial applications secondary.

The Significance

The Significance

What Made AlphaGo Different

Compared to Deep Blue:

Deep Blue defeated Kasparov through brute force calculation—200 million positions per second, overwhelming human ability to think ahead.

AlphaGo defeated Lee Sedol through something resembling intuition—learning patterns from millions of games, developing a sense of what moves "felt" right, then using selective search to verify intuitions.

This was qualitatively different:

Deep Blue couldn't learn or improve—it was programmed vs. AlphaGo learned continuously from self-play

Deep Blue's chess knowledge was hand-coded by experts vs. AlphaGo discovered strategies through learning

Deep Blue's victories felt like humanity was beaten by a calculator vs. AlphaGo's victories felt like witnessing a new kind of intelligence

The Philosophical Implications

Creativity and Intuition:

For centuries, creativity and intuition were considered uniquely human. We can calculate, sure, but machines can do that faster. Our advantage was in insight—seeing patterns, making leaps, creating novel solutions.

Move 37 challenged this. That move was creative. It was unexpected, beautiful, and beyond what humans would conceive. If machines can be creative, what remains uniquely human?

Learning vs. Programming:

AlphaGo succeeded not through hand-coded expertise but through learning. Given enough computing power and a learning algorithm, it discovered Go strategies through self-play.

This suggested a path to artificial general intelligence: don't try to program intelligence directly. Instead, create learning systems that develop intelligence through experience.

Understanding vs. Calculation:

Did AlphaGo "understand" Go? Its neural networks recognized patterns, its tree search explored consequences. But did it understand what territory is, why capturing stones matters, the aesthetic beauty of elegant play?

This question remains unresolved. AlphaGo performed like an expert who understands deeply, but its internal representations are alien—millions of weights in neural networks with no obvious connection to human concepts.

The Human Response: Wonder, Not Fear

Unlike Deep Blue (which generated anxiety about human obsolescence), AlphaGo inspired more positive reactions:

Awe and Beauty:

Go professionals spoke of AlphaGo's play as beautiful. They studied its games with reverence, learning from it like students from a master.

Fan Hui: "I learned something beautiful from AlphaGo. It played moves I would never have thought of. It's like discovering a new layer to Go."

Collaboration, Not Competition:

Rather than fearing AI replacing humans, many saw opportunity for collaboration:

Humans using AI to improve

AI revealing new strategies humans could adopt

Joint human-AI analysis producing insights neither could alone

Appreciation of Human Qualities:

Paradoxically, AlphaGo highlighted what's special about human Go:

Lee's Move 78 showed human creativity finding machine blind spots

The emotional drama, psychological struggle, and narrative of the match—all human elements

The community's shared experience, collective learning, and cultural meaning of Go

AlphaGo plays better Go, but humans give Go meaning.

Impact on AI Research

AlphaGo demonstrated several key principles now central to AI:

1. Reinforcement Learning Works:

Learning through trial and error (reinforcement learning), particularly self-play, can achieve superhuman performance.

2. Combining Approaches:

Integrating deep learning (for intuition/pattern recognition) with tree search (for planning) is powerful. Neither alone would have succeeded.

3. Transfer and Generalization:

The path from AlphaGo → AlphaGo Zero → AlphaZero → MuZero showed that general learning principles could master diverse domains.

4. Compute Scaling:

Performance improved predictably with more computing power and more training. This "scaling hypothesis" has driven subsequent AI development.

These insights influenced everything from large language models (GPT-3/4, ChatGPT) to protein folding (AlphaFold) to robotics.

Acceleration of AI Progress

AlphaGo's victory accelerated AI development and investment:

Funding Explosion:

Global AI investment increased dramatically

Companies and governments raced to develop AI capabilities

AI arms race rhetoric intensified

Talent War:

Competition for AI researchers intensified

Top researchers could command salaries of $1M+

Universities struggled to retain faculty against industry offers

Public Awareness:

AI moved from niche concern to mainstream awareness

Discussions about AI safety, ethics, and impact intensified

Both optimism and concern about AI's trajectory grew

China's Response:

China viewed AlphaGo as a wake-up call. The match was broadcast widely in China, which has a strong Go culture.

Shortly thereafter, China announced massive AI investment plans, seeing AI as critical for economic and military competition.

The match arguably influenced China's national AI strategy.

The Future

The Future

After claiming the title of world champion of Go, AlphaGo continued to play competitively. Today, its successors are building upon AlphaGo's legacy to help solve increasingly complex challenges that impact our everyday lives, not just Go mastery.

These systems include AlphaZero, MuZero, and AlphaDev. They represent three distinct leaps: mastering perfect-information games (AlphaZero), learning world models without knowing the rules (MuZero), and inventing new low-level algorithms that outperform decades of human engineering (AlphaDev). With these AI systems from DeepMind, Google is moving from superhuman gameplay to real-world optimization and algorithm discovery.

AlphaZero: Expanding Beyond Games

AlphaZero’s future isn’t about beating stronger chess engines. That frontier was conquered in Seoul. Its next evolution is about strategy in the real world. Expect it to move into domains where decisions unfold like games but with higher stakes:

complex logistics and routing

multi‑agent negotiations

scientific discovery framed as strategic search

large‑scale planning problems in energy, transportation, or materials

AlphaZero’s legacy becomes a blueprint for general strategic reasoning, not just gameplay. It’s the ancestor of systems that help humanity navigate vast decision spaces we can’t fully grasp.

MuZero: The Universal Simulator

MuZero’s defining trait—learning the rules of an environment without being told—points toward a future where it becomes a universal model‑builder. Expect it to evolve into systems that can:

learn physics‑like rules from raw sensory data

simulate complex environments for robotics

adapt to unfamiliar domains with minimal human input

serve as the “imagination engine” inside more general AI systems

MuZero’s descendants will likely power agents that can predict, plan, and adapt in real‑world settings where uncertainty is the norm. It’s the seed of AI that can understand the world the way animals do; through interaction, not instruction.

AlphaDev: Becoming a Creative Engineer

AlphaDev’s future is the most radical. It showed that AI can discover new algorithms, something once thought to be the exclusive domain of human ingenuity. Expect its successors to:

design new data structures

optimize compilers and hardware‑software interfaces

invent cryptographic primitives

generate domain‑specific algorithms for physics, biology, or finance

co‑design hardware and software in a unified search space

AlphaDev’s lineage points toward AI that expands the frontier of computer science itself, discovering optimizations and structures that humans would never think to explore.

Together, these three systems hint at a future where AI doesn’t just perform tasks, it strategizes (AlphaZero), understands (MuZero), and creates (AlphaDev). This progression suggests the development of increasingly general, increasingly autonomous systems capable of learning the rules of new domains, planning across long horizons, inventing new tools and algorithms, and collaborating with humans on scientific and engineering breakthroughs. They are early prototypes of AI that can navigate, interpret, and reshape the world.

Stay tuned as DeepMind nurtures the children of Go master, AlphaGo.

The Revolution

The Revolution

Go mastery was revolutionary for AI because it shattered the long‑held belief that some domains were simply too complex, too intuitive, or too "human" for machines to conquer.

For decades, Go had been the final frontier. It was the one game whose astronomical search space and reliance on intuition made it immune to brute‑force computation. When AI finally mastered it, the field crossed a psychological, scientific, and technical threshold that changed everything. The search space is enormous: far larger than chess. There are more possible Go positions than atoms in the observable universe. Human intuition mattered: top players relied on pattern recognition, flow, and "feel," not just calculation. Traditional AI failed: symbolic reasoning, handcrafted heuristics, and classical search all broke down. For decades, Go was the game that humbled AI.

What Made Go Mastery Revolutionary

1. It proved that deep learning plus reinforcement learning could outperform human intuition. AlphaGo didn't win by brute force. It learned patterns from millions of positions, strategies through self‑play, and value estimates that approximated long‑term outcomes.

This was the first time an AI system demonstrated creative, non‑obvious strategic insight at superhuman levels.

2. It showed that neural networks could guide search in enormous decision spaces. Monte Carlo Tree Search (MCTS) had existed for years, but combining it with deep neural networks was a breakthrough. The networks pruned the search space, making previously impossible computations tractable. This hybrid architecture became a blueprint for future AI systems.

3. It validated self‑play as a pathway to mastery. AlphaGo Zero and AlphaZero learned from scratch with no human data and no expert games. This was a paradigm shift, for AI could now invent knowledge rather than inherit it. Self‑play became a general recipe for superhuman performance in Go, Chess, Shogi, Atari, StarCraft II, and protein folding (via AlphaFold's training dynamics).

4. It demonstrated that AI could discover strategies humans had never imagined. Move 37 in Game 2 against Lee Sedol became iconic because it was unconventional, strategically brilliant, and outside human professional playbooks. This was the moment many realized AI could be creative in a meaningful sense.

5. It changed the world's perception of AI overnight. Chess mastery in 1997 felt like a computational triumph. Go mastery in 2016 felt like a cognitive one. It triggered a surge of investment in deep learning, a shift in research priorities, and a cultural awakening to AI's accelerating capabilities.

The Broader Impact

Go mastery wasn't just a milestone. It was also a signal. It told the world that intuition can be learned by machines, complex reasoning can emerge from data and self‑play, and the boundaries of AI capability were far more fluid than expected.

It marked the end of the "AI can't do that" era.

Links

Links

IBM's DeepBlue defeats Kasparov at chess. IBM's checkers was the world's first self-learning checkers program and the first AI program.

AI game playing page has more info on other games.

More moments that matter in AI's development.

External links open in a new tab:

- Large Magnetic Go Game Board Set from Amazon

- deepmind.google/research/breakthroughs/alphago/

- linkedin.com/pulse/alphago-game-changing-ai-mastered-go

- illumin.usc.edu/ai-behind-alphago-machine-learning-and-neural-network/

- timelines.issarice.com/wiki/Timeline_of_AlphaGo

- en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Computer_Go

- latimes.com/world/asia/la-fg-korea-alphago-20160312-story.html

- en.wikipedia.org/wiki/AlphaGo

- britgo.org/computergo/history